Women in Sci-Fi History

Maddd Science

As most of you know, I run an art blog dedicated to 70s-era sci-fi art. I've posted over 23,000 pieces since 2013. And 70s-era sci-fi artists, based off that data, were mostly men.

I can list the women I know off the top of my head in 70s sci-fi art on one hand: Jeffrey Catherine Jones, Wendy Pini, early Rowena Morrill, half of Leo and Diane Dillion.

And my old standby for artist indentification, the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, wasn't much help for once (although I did learn that the tag "confronted by murdered woman" has been used for four seperate entries).

But that's just based off what I've surfaced. Part of it's my poor memory... I just remembered Barbara Remington's awesome 1965 Lord of the Rings triptych, for example. But I'm likely missing plenty of women artists who got erased in addition to the ones weren't able to break through at all. And I actually uncovered a new slightly-lesser-known sci-fi artist, April Lawton, the other week, which goes to show how much I know. If you have a favorite women sci-fi artist active around the 60s-80s, I'd love to hear about her! Email me here or tweet me.

The anthology review linked here covers that phenomenon within written science fiction in the early 20th century. I only excerpted a couple (hefty) paragraphs below, but the whole thing is great, offering a lot of the data and context you need in order to temper the sexist backlash this sort of explanation inevitably garners.

A Universe of One’s Own

Nicole Rudick, The New York Review of Books

In Partners in Wonder, Davin has compiled an impressive amount of data, dismissing anecdotal notions about the era with facts, but he sometimes misses the forest for the trees. He is harsh on second-wave feminists who, he says, created the myth of a sexist patriarchy in science fiction. “They were not able to see back, beyond the early-Sixties contraction, to that female past,” he writes, “because their mythology said it had never existed.” But how readily available were copies of SF magazines from the Forties and Fifties to women in the Seventies? (Damon Knight observed that “once a magazine goes off sale, it’s gone.”) In looking back, feminists would not have glimpsed a bulb that had dimmed over time, but merely a pinprick of light.

The history of literature is a history of publication—who gets published, in what form, by whom, and when, a host of factors that conspire to determine whether an author gains renown or disappears from the literary landscape. If we examine the history of literary achievement (a critical mass of awards, magazine profiles, reviews, inclusion in anthologies and course offerings), it is largely white, male, and middle class—a homogeneity enabled by a similar constituency in the editorial departments of periodicals and books. In Silences, her groundbreaking 1978 survey of the American publishing industry, Tillie Olsen found one female writer of achievement for every twelve male writers. The gender and racial makeup of publishing in all its forms is beginning a slow shift (with quite a long way to go), and with it has come a wealth of rediscovered voices, many of them female, and in a variety of genres.

Here's a romp through the tough-to-define proto-sci-fi genre, i.e. anything before Frankenstein:

The Science Fiction That Came Before Science

Edward Simon

Godwin, Cavendish, and their contemporaries are important for generating a freely speculative space of imagination—which is still science fiction’s role today. In constructing worlds—or birthing “paper bodies,” as Cavendish called them—the authors’ acts of envisioning possible futures had a tangible impact on how reality took shape. Take this selection of technological marvels Bacon describes in New Atlantis: “Versions of bodies into other bodies” (organ transplants?), “Exhilaration of the spirits, and putting them in good disposition” (pharmaceuticals?), “Drawing of new foods out of substances not now in use” (genetically modified food?), “Making new threads for apparel” (synthetic fabrics?), “Deceptions of the senses” (television and film?).

Speaking of pop culture hating women, this next article has spoilers for Once Upon a Time in... Hollywood, so skip it if you care about that.

Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood Is Yet Another Tarantino Revenge Fantasy

K. Austin Collins, Vanity Fair

But then comes that ending, and those flames, and the implicit through-line they strike from Basterds to Hollywood. It lends itself to the interpretation that the Manson murders—famously a signifier of the era’s end of innocence—might, for Tarantino, be an event commensurate with the violence of WW II or American slavery. Not because the murders are "just as bad" as those atrocities—I don’t think Tarantino believes this—but because the consequences of all three have long been the substance of modern movies. Genre-wise, it checks out: Images from the slave era would meet their discursive match in the gritty black empowerment of the Blaxploitation era, a key influence for Tarantino, and WW II has of course been the stuff of movies from the moment the first newsreel dispatches from overseas hit American theaters. 1969, meanwhile, speaks for itself.

Up next: A takedown of all those people who like to use the term "elevated horror."

Gentrified Horror

Henri de Corinth, Lo Specchio Scuro

Comments such as these made from the perspective of demand for cultural capital, and represent a kind of gentrification of horror that has taken place. The film distribution apparatus, the critical establishment, and their audience that together since the early 1980s had systematically ghettoized the horror and exploitation genres have since the mid 2010s gradually reclaimed them. A neighborhood that had been systematically deprived of resources and avoided by patrons for decades has been ‘revitalized’ (it is not a coincidence that film critics, when referring to genre cinema, will often use the same language as real estate developers). Horror for the bourgeoisie co-opts the image and conventions of horror while at once eschewing the visceral thrills and sensibilities of horror, deeming itself suitable for consumption by “…an audience that otherwise would not go to see a horror film.”

Here's an article packed with spoilers about the new Veronica Mars season, which was a lot of fun, even if it can't recapture the magic of the first season.

Free Solo: On the return of ‘Veronica Mars’ and the power of the solitary woman

Soraya Roberts, Longreads

The original cut of the Veronica Mars pilot had a cold open set to “La Femme d’Argent,” the first track from AIR’s 1998 debut album, Moon Safari. A neon take on noir, the scene has the 17-year-old titular blond (Kristen Bell) alone in her car in the middle of the night outside Camelot, one of her local “cheap motels on the wrong side of town.” Her camera — along with a calculus textbook — sits on the passenger side and her lips are glossed as she watches through the rain-streaked window of her convertible. The silhouette of a couple can be seen having sex in one of the motel rooms. “I’m never getting married,” she says.

Finally, an article exploring the problems that film lovers face now that subscription video on demand has surplanted buying and renting physical media. I'd love to do a version of this article that replaces film snobs with B-movie lovers. It'd probably make all the same points, really, but it would have a lot more Class of Nuke'Em High poster art.

The Film Snob’s Dilemma

Elisabeth Donnelly, Vanity Fair

“It feels like everything is at our fingertips, but in our cloud-based system that’s such an illusion,” Nicholson said. “What makes me really nervous is that there’s nothing to say that Netflix couldn’t do what they did already, when they had a DVD library that made you feel very safe. That’s why we allowed video stores to go out of business like they did. But they suddenly destroyed their DVD market and limited the amount of movies that they offered, and we were in a complete drought of old, classic movies.”

Aaand that's all! I'm trying to stick to shorter emails moving forward, in the hope that it means I'll be able to send them more regularly. Granted, I'm more optimistic about the "shorter" part than I am about the "regularly" part.

Next Time on Maddd Science: Sylvie and Bruno

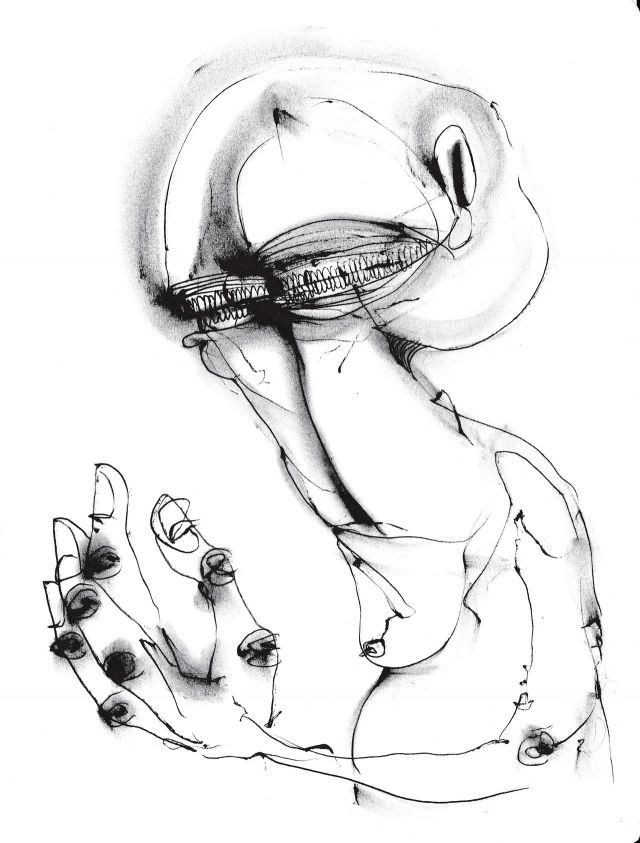

Header image: “Ma Grendel,” by Daniel Williams.

Like this issue? Maybe forward it to someone you think would like it, too. My marketing budget just covers that and my twitter account. If this is the first time you're reading this, you can subscribe here! If it's the last time you're reading this, you can unsubscribe using the button below!