Interview: Rick Sternbach's Dolphin Suit

Rick Sternbach has a long legacy in science fiction art.

He co-founded the Association of Science Fiction and Fantasy Artists in 1976 and the non-profit International Association of Astronomical Artists in 1981. He won the 1977 and 1978 Hugo Awards for Best Professional Artist. He was Assistant Art Director and Visual Effects Artist on Carl Sagan's Cosmos: A Personal Voyage series from 1977-80. He worked on The Last Starfighter, Steven Soderbergh's Solaris, and (his biggest impact) has had a long career behind the scenes of the Star Trek franchise.

He started in the art department for Star Trek: The Motion Picture and then designed for The Next Generation, eventually becoming a Technical Advisor for the franchise up until Enterprise. Some of the designs based off of Sternbach's work include: phasers, tricorders, PADDs, the communicator badge, and the USS Voyager.

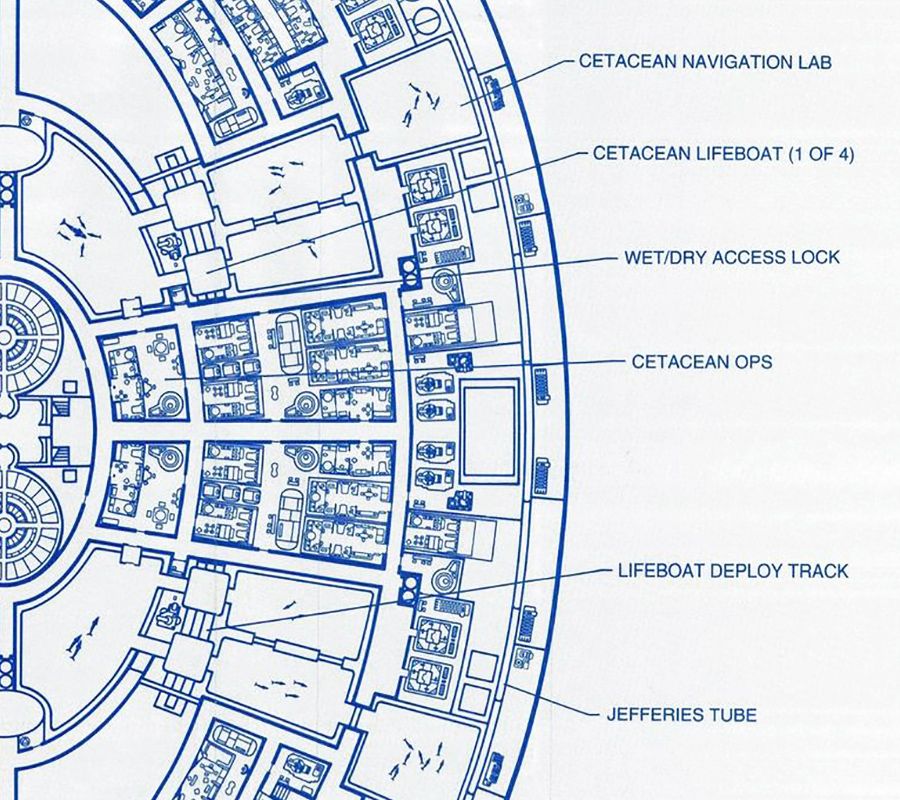

While working on TNG, Sternbach slipped in references to a "cetacean ops" onboard the Enterprise, a concept that is probably more familar to today's Trek fan due to its reappearance much later in the show Lower Decks. The cetacean facility is referenced in the TNG episodes "We'll Always Have Paris" and "The Perfect Mate."

Sternbach put cetacean ops into a few guidebooks as well:

It's now canon in Star Trek that the Enterprise has marine mammals operating onboard in some capacity, and this is due to Sternbach's lifelong dual interests in outer space exploration and marine biology.

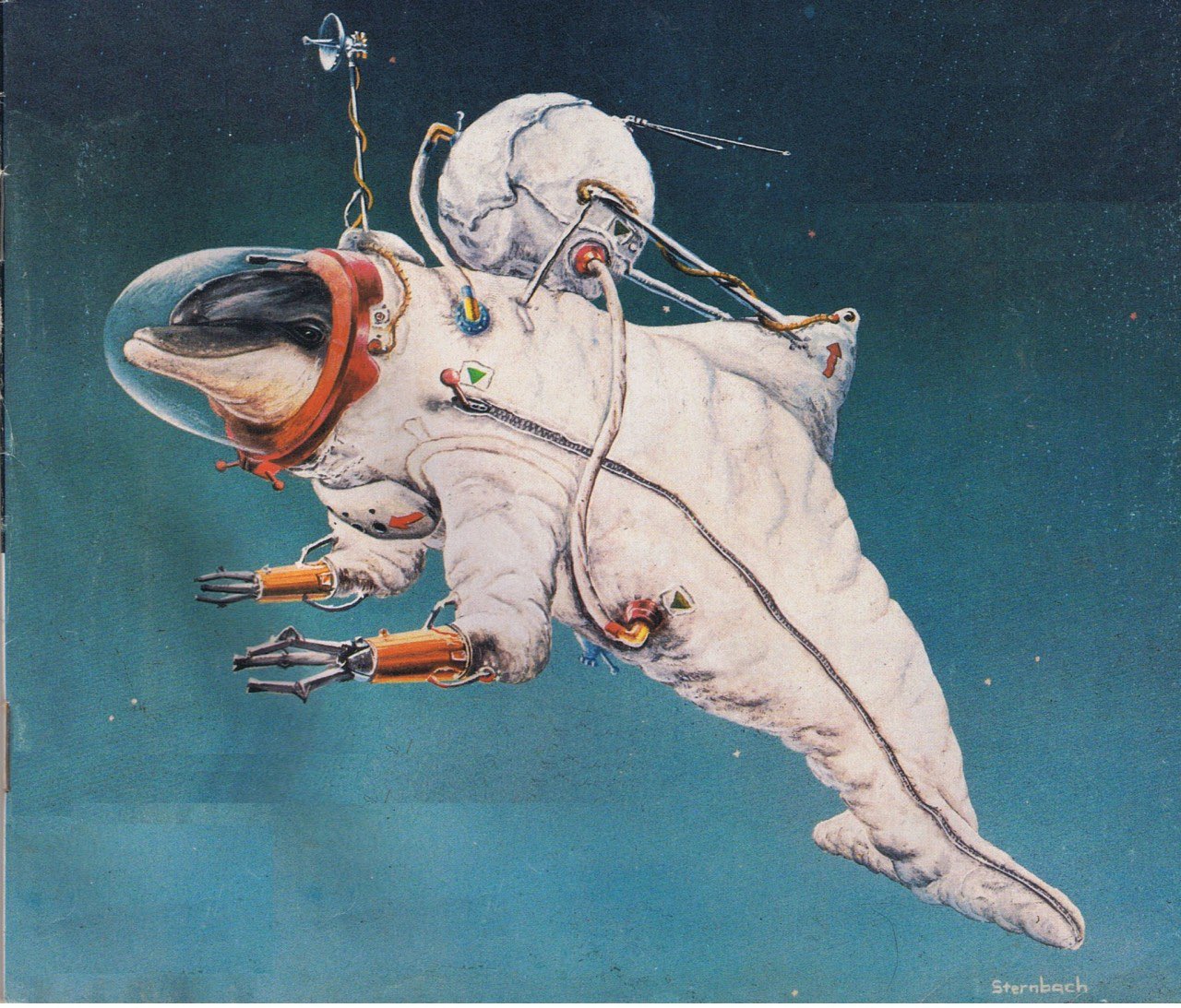

That's also why he designed probably the best retro sci-fi illustration I've seen of a dolphin in a spacesuit.

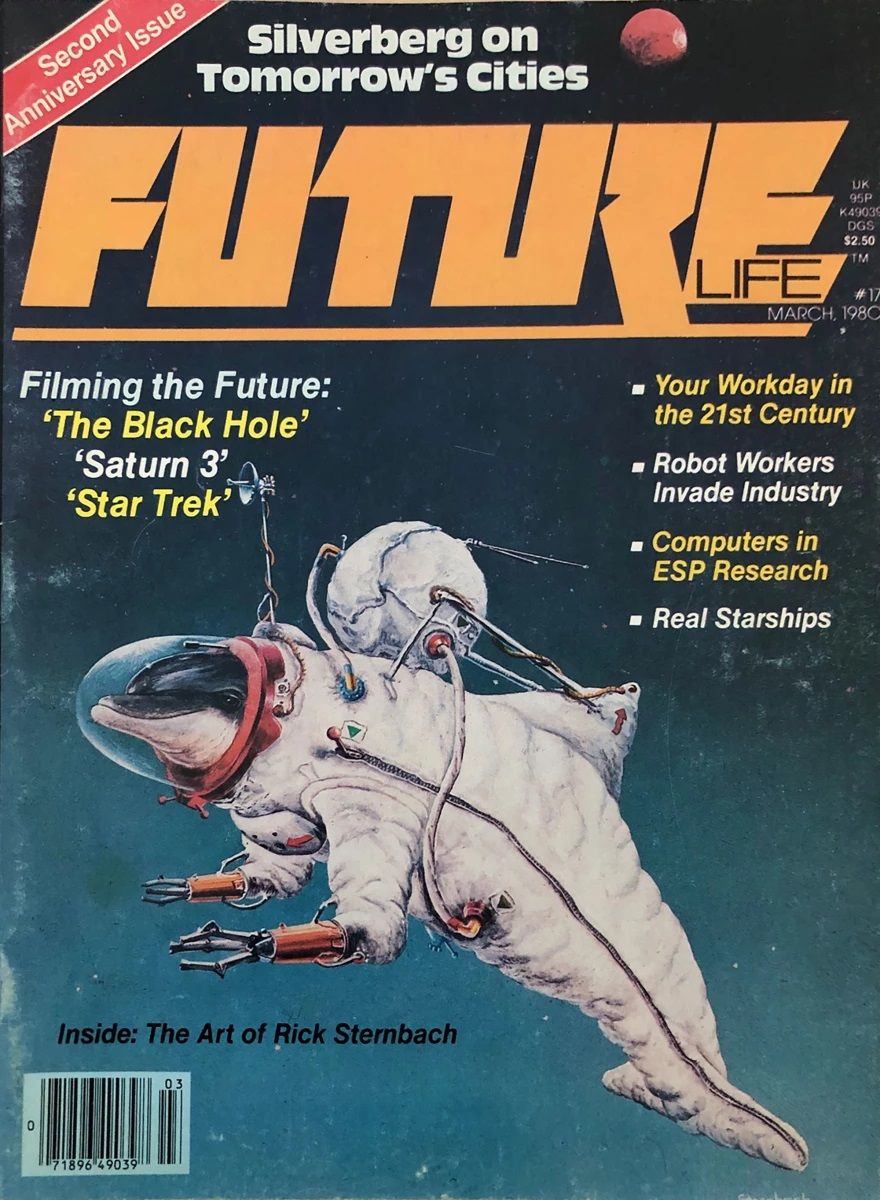

Sternbach's illustration "Cetacean Tomorrow" first appeared in print in the March 1980 issue of Future Life magazine, for a cover story profiling Sternbach himself. He came up with the idea for the illustration for fun, so presumably that cover was the only way to get it into print.

Here's the quick email interview response (complete with emoji) that Sternbach kindly gave me when I asked for any insight he might have on the design of the suit.

__

The following is what I recall; might have similar bits in the magazine but this should be quotable. 😊

Back at the University of Connecticut, I began considering art as my major in the fall of 1969 after having developed a love for space exploration and astronomy and science fiction as a kid growing up in the 50s.

A couple of years in at UConn, I had a growing interest in biology, specifically marine life, and even more specifically whales and dolphins. And that led me to the crazy change of major from art to bio, with an additional three year plan to see it through. Didn’t happen, and I left UConn in the early 70s as I was meeting a great many scientists, engineers, SF authors, and other artists, and I was able to sell my work to science fiction and astronomy magazines and book publishers.

*

But the interest in cetaceans continued, and in 1974 I began thinking about what it might take to protect a bottlenose dolphin in a pressure suit. This raised so many questions, not the least of which was if we could ask them pretty please to join us in space.

The suit engineering would be majorly complicated, but that was the fun part for me. I had been told that Tursiops shed maybe an entire layer of skin per day, so the water filtration gear would need to be able to handle that. Their echolocation wouldn’t work in a vacuum, so a sonar-to-radar system would need to be designed. Their vocalizing would need to be worked into the radio communications. Manipulators would be added.

*

This was all an interesting exercise, and today not something I would ever actually propose, given some of the things done to marine mammals over the decades. But it was still a fun SF concept.

Rick

__

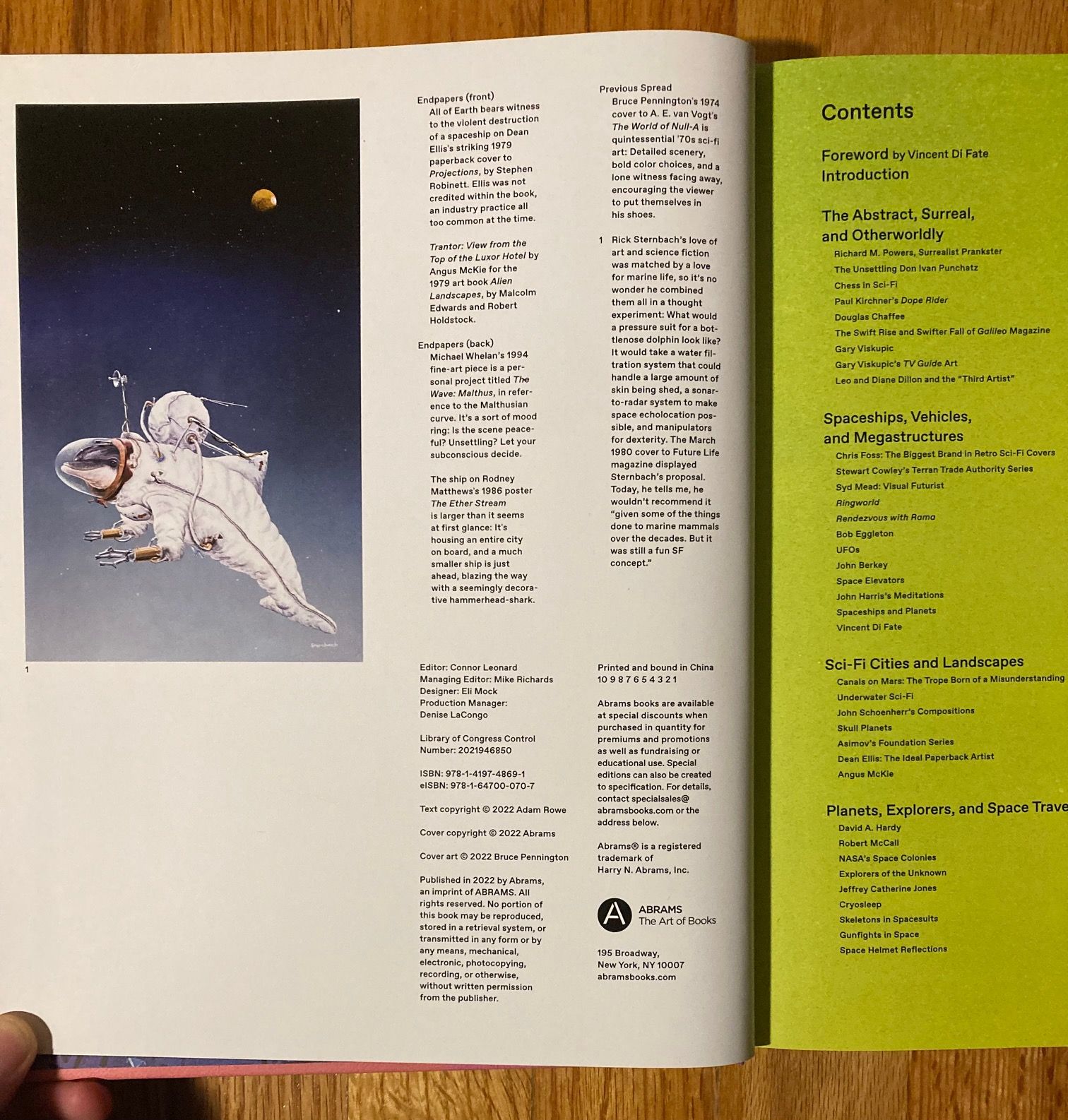

I don't have an entire section on space dolphins in my upcoming art book, but I always loved that illustration, so when I got in touch with Rick Sternbach late in the process of writing my book, I asked him if I could get permission to use it anyway, and I squeezed it in.

It'll appear all by itself on my copyright page, which I think is fitting, since both that illustration and this book are labors of love that were willed into existence without anyone exactly asking for them.

And if you squint, you can read my caption, which is the boiled-down version of the interview above.

__

I also looked up Sternbach's Future Life profile – The internet archive has both a scanned and a plain text version.

Fun facts from the article: He was inspired by Chesley Bonestell's space art (not a surprise, as a huge amount of 70s sci-fi artists cite Bonestell as an inspiration), and was further inspired to get into the film industry by Ralph McQuarrie's Star Wars concept art. Also, he named one of his cats "Virgil Finlay," a reference to another great early sci-fi artist.

Here's an excerpt that discusses the dolphin suit:

This vision, which he titles “Cetacean Tomorrow,” may at first appear more comic than cosmic, but Rick has concocted a nearly believable explanation for his imaginative scene: “He’s a Pacific Bottlenose Dolphin, Tursiops gilli ,” Rick says, “born on December 3, 1985, at the San Diego Marine Mammal Facility of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The dolphin has been trained to use a pressure suit specially developed for space-traveling cetaceans. The suit contains a radar-to-sonar converter so the dolphin can scan in-space objects the same way he would underwater. It’s also outfitted with a radio, an attitude control system using liquid nitrogen gas jets, a water circulation system and filter to keep his skin wet and clean (dolphins generate almost an entire layer of skin every day), and finally, a set of manipulators for working inside and out.”

It may sound strange, but Rick’s intent is not idle fantasy. “The theoretical capabilities of both the suit and the dolphin have been checked out by cetacean trainers and veterinarians,” Rick reports. “They all agreed that it’s ‘different,’ but nobody could see any major obstacles.”

Although he is best known for larger-scale spacecraft, Rick’s one-dolphin spaceship is a good illustration of his curiosity about, and attention to, the factual framework of the sci-fi scenes he paints.

__

There's way, way more left to say about science fiction's relationship to dolphins, particularly around the '60s-90s. I'll get around to digging into the connections in this newsletter at some point. Until then, you can satisfy the urge to see more here: I've been posting a sci-fi dolphin artwork (almost) every Saturday this year.

Here are some of the best suits I've posted so far, arranged in order of how much they remind me of Sternbach's concept. First up, Richard J. Bartrop’s 1994 cover art for Freeflight #4 has extra mechanical arms.

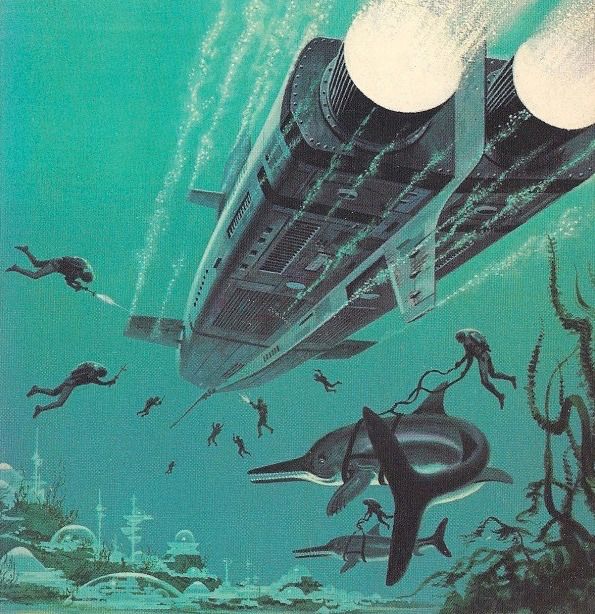

David Cherry’s 1985 frontispiece to David Brin’s Startide Rising also features gripper arms, and might be the most beautiful sci-fi dolphin artwork:

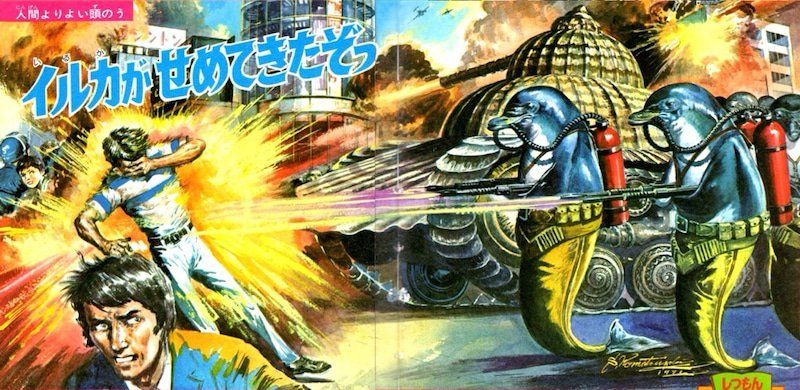

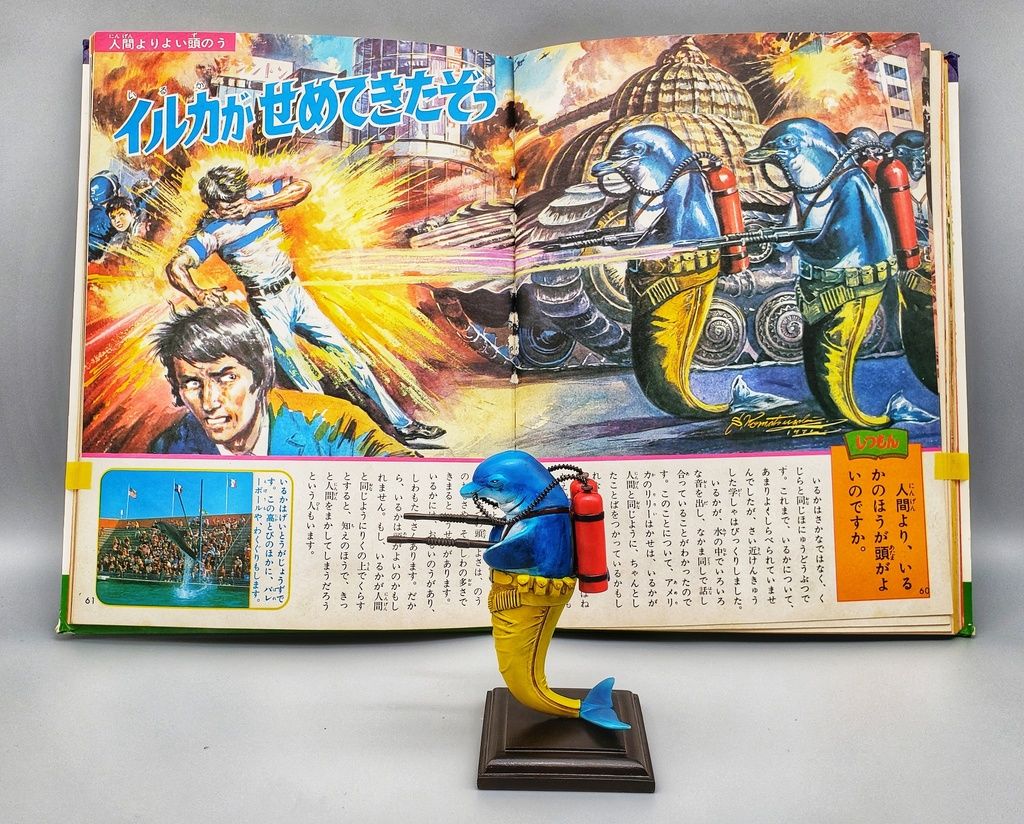

The earliest dolphin suit illustration might be this 1971 one by Shigeru Komatsuzaki. It's definitely the only one with a seashell-themed tank.

That illustration was apparently turned into a bit of a meme in Japan, to the extent that someone made a $50 Komatsuzaki-estate-approved scale model kit in 2022. It's out of stock at the moment, sadly.

David Brin’s Startide Rising is behind the best dolphin suits: Here’s the very first edition cover, by Jim Burns in 1983.

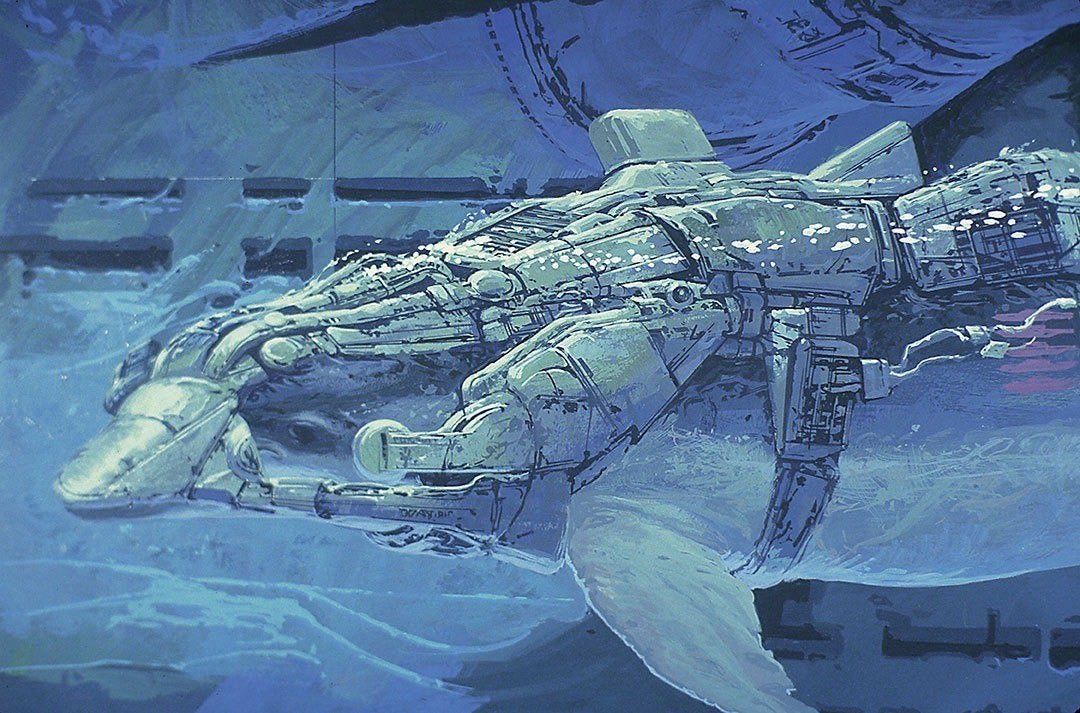

Design futurist Syd Mead even did a dolphin suit with this 1993 Johnny Mnemonic concept art.

Finally, an honorable mention goes to these Ichthyosaurs and their Atlantean harnesses on this 1978 Dean Ellis cover art for ‘Attack From Atlantis’ by Lester Del Rey.

That's it for this week! Buy my book!