When Genre Tropes Go Bad

Maddd Science

I really wanted to title this letter "When Good Tropes Go Bad." I can't, though! Because the point I'm making here is that when we realize tropes are rooted in some kind of nasty prejudice, they don't become bad, they were just that bad all along.

Anyway, as someone who's obsessed with the process of repurposing and reviving old retro storytelling tropes, it's something I think about a lot. We accept a lot of tropes today that have some shady pasts. That doesn't mean we can't use em! But I think the best genre writers today are the ones who understand their genre's history and can rework its tropes to avoid or subvert the worst of their past.

To my mind, a lot of the issues come down to how many tropes are pulled from real life. Horror monsters, for example: If you write a straightforward story about Salem's witches being real, you're kinda ignoring the real reason Puritans were getting together to harass the independent women in their midst.

Conspiracy theories also overlap with real life, making them tough to write about responsibly. Conspiracies have also kind of taken over the article lineup I have here today! As they say, give a conspiracy theorist an inch, they'll take a foot and blame it on the lizard people.

First, here's a good article that's tangential to the "pulp tropes bad" discussion, detailing how one CIA operative turned author channelled his fears of communism into some truly bonkers occult spy thrillers.

“The Devil Had Worshipers Long Before Lenin”: The Occult Spy Novels of E. Howard Hunt

Michael Grasso, We Are The Mutants

Hunt throws around an array of competing esoteric traditions—Western Satanism as personified by the Black Mass popularized in 17th century France, European witchcraft from the same period, Haitian vodou and indigenous African religion—combining them all into a vast, syncretic Communist-occult conspiracy.

Can Conspiracy Thrillers Work Under a Conspiracy Presidency?

Alan Glynn, Vulture

The conspiracy-theory aesthetic in fiction had a pretty decent half-life, but by the late 1990s it had more or less run out of steam. For one thing, people no longer found it shocking that those in power might be bad actors or that institutions, in the service of their own preservation, might routinely and reflexively work against the interests of individuals. And for another, conspiracy theory itself had become a devalued currency. Thanks mainly to the internet, the paranoid style was now back in force. Information overload led to a sort of heat death of what we know and understand, a point of entropy at which, if a conspiracy theorist believed one theory — chemtrails, say — they would most likely believe all of them: the moon landings, fluoridation, Waco, Lady Diana, the New World Order, WT7, take your pick.

Here's retro horror guru Grady Hendrix discussing his own shifting relationship to conspiracy theories. He makes a similar point as the last article, arguing that conspiracies have gotten darker and all-encompassing.

The H Word: Paranoia for Beginners

Grady Hendrix, Nightmare Magazine

When I was a kid, conspiracy theories were my safe space. I had a couple of books that collected the addresses of different groups and I’d sit in my room, writing away for literature from UFO cults like Unarius and the Raelians. The United States Postal Service was a cornucopia of crackpot conspiracies, disgorging pamphlets from Minnesota’s Warlords of Satan, Christian comics from Jack Chick, apocalyptic photocopied newsletters like The Crystal Ball, catalogs for underground books from Loompanics Press, MK-Ultra exposés from Finland, shocking revelations of CIA weather control photocopied by whistleblowers on company time.

I lost touch with the conspiracy community around Y2K, but in 2016 I checked back in to research my new book and walked into a horror movie, already in progress. The boards were full of talk about Pizzagate, bots, groomers, Beta alters, QAnon, and birthers. Nothing was funny anymore. Everyone felt out of control of their lives, they felt angry, they felt like drones enslaved by the one percent, and freedom wasn’t an ideal but a delusion for the sheeple. Basic human compassion for murdered children was snuffed out beneath talk of crisis actors and false flag operations.

On a related note, Grady's fiction deals in retro horror tropes without much subversion. His very straightforward use of demon possession in My Best Friend's Exorcism and conspiracies in We Sold Our Souls works, and it's because he's a lot more interested in his protagonists' psychology.

Personally, I'd argue that conspiracies have always had too much creepy baggage, regardless of how wacky and fun they used to seem. Here's an explanation for why you can't get to lizard people without stepping in a pile of anti-Semitism:

Your conspiracy theory is anti-Semitic

Miikka Jaarte, Varsity

A secretive group of people controls the banks, the media and the economy. They’re the Illuminati, the Freemasons or blood-drinking lizard-people from the Alpha Draconis star system, if you’re feeling adventurous. The main point is this: they control the world, subvert democracies, and possibly want to turn the world gay by putting chemicals in the water.

I hopefully don’t have to tell you that this is all horseshit. But I might have to tell you that these conspiracy theories, while not always explicitly anti-Semitic, tend to be deeply rooted in Nazi propaganda.

Speaking of reclaiming a genre from its history of prejudiced tropes: Horror streaming service Shudder has a new documentary about black horror films, Horror Noire. It's pretty great! Here's a Q&A with the author of the book its based on, but you should just sign up for a free trial of Shudder and check out the doc yourself.

Horror Noire and the Legacy of Get Out Two Years Later

Jordan Crucchiola talks to Dr. Robin R. Means Coleman, Vulture

Q: The documentary takes care to emphasize the beauty and strength of black folks in horror when they’re actually represented well. And one of the most satisfying things about Get Out was how deliberately it embraced some of those elements while dismantling some of the worst clichés about black characters in horror — the brutal buck, the removal of any interiority, existing only among urban decay. What are some of the tropes you would say need to be left behind the fastest as black horror proliferates in pop culture?

A: Here’s what I hope we leave behind, and this has to do with what we see happening in the 1980s. As we continue to reimagine movies like Halloween, Poltergeist, Friday the 13th, all of that is born out of white flight. Whites were fleeing the urban to the suburban, and then we were invited to look in the mirror at the monstrous. But in doing that they implicated black and brown bodies. In The Shining, the Overlook Hotel is built on an Indian burial ground. Poltergeist, it’s an Indian burial ground. We’ve got Pet Sematary coming back out again, and even in this period of white flight, black and brown folks are implicated in the evil and the horrific; there’s something so oddly overly religious and deficient about all of us that it seeps in even centuries later and taints whiteness. I’d like to see that go away.

Still with me? Here's a much more innocent trope to read about:

The Weird Rom-Com Trope No One Talks About

Harling Ross, Manrepeller

Here we were as a society, all along thinking dramatic airport declarations of love and sex scenes where women keep their bras on and easily solved misunderstandings were the main tropes of romantic comedies — but nope. Weird roommates take the cake. As for why, I have a number of theories.

Here's a fun biography of a linguist who's work shaped our understanding of how 1930s criminals spoke.

David Maurer, The Dean Of Criminal Language

Sarah Weinman, Crime Reads

A United Press wire story from April of 1932 reported that Maurer racked up a glossary of “more than 500 words, used by thieves, racketeers, and other underworld characters.” At that stage, said Maurer, criminal argot sprung up so that “conversations among hoodlums and prisoners might be more guarded.” And some of the slang Maurer wrote down still carries over today: “grease” for protection money; “box” or “crib” for a safe; “artillery” for firearms; and “moll” or “skirt” for women in the underworld. Maurer also decreed, based on his research, that Youngstown, Ohio had “the hardest collection of individuals I ever want to see.” Needless to say, this judgment did not go over well with the local police, whose chief vowed to clean up the city and beef up the force, even as he protested: “there hasn’t been a gang killing in over a year.”

How ‘Die Hard With A Vengeance’ Caused The FBI To Re-Think The Federal Reserve’s Security

Andrew Husband, Uproxx

This one scene, our FBI guy said, “You know it sounds crazy, but somebody could actually pull this off. We’re going to actually have a sit-down [meeting] and talk about how we can improve the facility so that it could never happen.” That pleased me, actually.

Unrelated to anything, here's the nerdiest thing I've seen in a while: a website dedicated to mathematical fiction.

I've been running the 70s Sci-Fi Art blog for about six years now, and have found that a few topics are consistently big traffic drivers: Star Wars and Alien, for example. The biggest one is Jodorowsky’s Dune. For some reason, I've never really gotten into it or cared much about it, even with the remake coming up. Here's an article arguing that I shouldn't:

Jodorowsky’s Dune Didn’t Get Made for a Reason… and We Should All Be Grateful For That

Emily Asher-Perrin, Tor.com

It’s no great tragedy that Jodorowsky’s Dune never got made. Everyone involved went on with their highly successful careers anyhow, and we arguably got a better film out of it—because Dan O’Bannon, Moebius, Chris Foss, and H.R. Giger all went on to create Alien. But if there’s one thing the world definitely doesn’t need, it’s more praise for the murky genius of men who compare Frank Herbert’s writing to Proust. (Jodorowsky did this. I can’t think of a writer who Herbert is less comparable to than Proust, except maybe Sylvia Plath or D. H. Lawrence.) Art doesn’t have to be a Sisyphean feat in order to mean something, and while it’s always intriguing to mull over what might have been, a better version of our timeline is not automatically waiting at the other end.

Next Time on Maddd Science: Dunking on Holmes

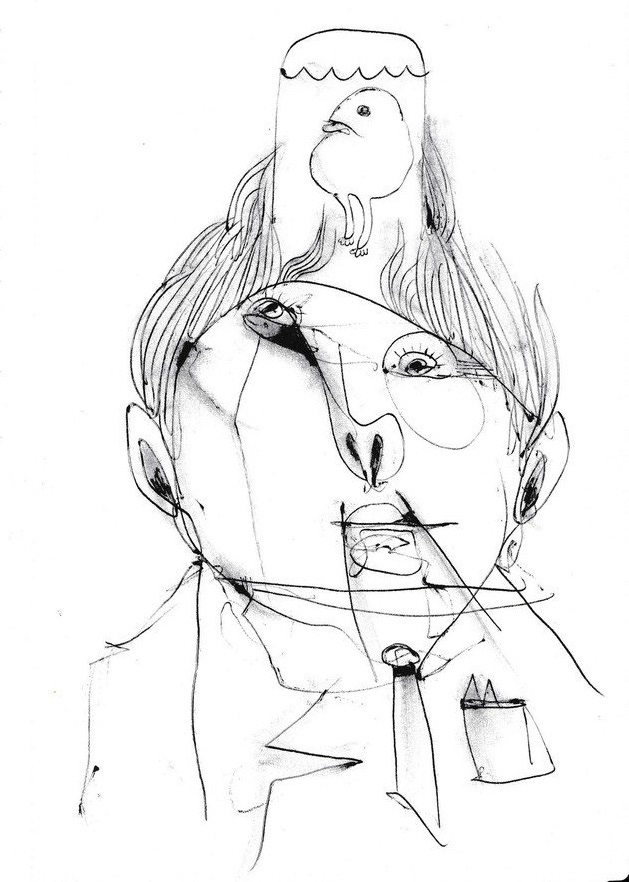

Header image: “Airing a grievance,” by Daniel Williams. I'm reinterpreting it as a genre trope in its natural state, suctioned to someone's brain.

Like this issue? Maybe forward it to someone you think would like it, too. My marketing budget just covers that and my twitter account. And if someone forwarded this to you, you can subscribe here!