Spoilers = good?

Maddd Science

Infinity War is possibly the best example of a film that really can be meaningfully spoiled, and I think it's because the plot twists and jokes are the best things worth discussing about the film once you've seen it. The movie isn't about being a movie so much as being a huge franchise-extension crossover event.

But that's just why I don't think people should care as much about movie spoilers as they seem to: Because most movies are about a experience deeper than anything a spoiler can affect. I mean, I enjoyed watching The Sixth Sense years after learning what the twist was, and that movie wasn't even particularly deep.

Spoiler alert: spoilers make you enjoy stories more

Andy Murdock, UC Newsroom

Intuitively, killing the surprise seems like it should make a narrative less enjoyable. Yet research has found that having extra information about artworks can make them more satisfying, as can the predictability of an experience. So Christenfeld decided to put spoilers to the test in the most straightforward way possible: by spoiling stories for people.

[..]

No one watches a romantic comedy truly wondering if the couple will be happy in the end. With a detective story, you can safely assume the detective will eventually solve the case.

“The point is, really we're not watching these things for the ending,” said Christenfeld. “I point out to the skeptics, people watch these movies more than once happily, and often with increasing pleasure.”

Why it’s time to stop the anti-spoiler paranoia

Todd VanDerWerff, The AV Club

The rise of anti-spoiler culture, then, can be tied to the rise of the Internet, which also gave rise to the sorts of viewers who actively seek out spoilers, even for projects that won’t hit screens for years to come. But it’s also closely tied to films like The Sixth Sense or TV shows like Lost, projects where major plot points are ideally kept secret for viewers’ benefit—projects where knowing there’s a twist is just as much of a spoiler as knowing what that twist is.

[...]

In a 2006 blog post pushing back against spoilerphobia, film critic Jonathan Rosenbaum argues that this “preserve the twist at all costs” sentiment is a recent development also. He points to novels like Don Quixote and the works of Charles Dickens as examples that largely gave away plot points in their chapter headings, which is to say nothing of plays like The Taming Of The Shrew or Death Of A Salesman, which give away their endings right there in the title.

The enduring popularity of Sherlock Holmes could be because Doyle set up a cast of interesting archetypes and then barely used any of them for more than a couple stories. It spurs imaginations, generating all the fanfic-y franchise extensions that have kept Holmes alive and the most filmed fiction character ever. Maybe if Doyle had cared more about establishing actual character arcs it would have discouraged everyone else from writing within the universe. Reminds me of how the X-Files' inability to develop Mulder and Scully's relationship wound up immortalizing it.

Anyway, here's a related article:

Moriarty Was An Afterthought

Eileen Gonzalez, Bookriot

Despite allegedly being the greatest criminal mastermind in London—“the Napoleon of Crime,” as Holmes so famously describes him—Moriarty’s existence isn’t so much as hinted at until The Final Problem. That’s two novels and twenty-three short stories after Holmes’s debut.

[...] In real life, it came from Doyle’s desire to be rid of Sherlock Holmes, a character he’d grown tired of writing. And so he conjured an all-powerful antagonist from thin air and threw him into the story with his usual bored disregard for continuity.

Abstraction in Science Fiction

Kirsten Zirngibl, personal blog

Thought experiment: You are a hunter-gatherer living 100,000 years ago, intimately familiar with the land you grew up on. Then, as an adult, you are suddenly teleported to Times Square, 2017. How would you process this environment? Without anything like this in your library of experiences, you would probably read the your surroundings as mostly abstract, instead perceiving the overall level of complexity. You might notice details ignored by everyone else, simply because you don’t know what should be prioritized. After studying things for a bit, you could still pick up on patterns and form theories of what is going on, but probably without a lot of confidence that you’re right.

[...]

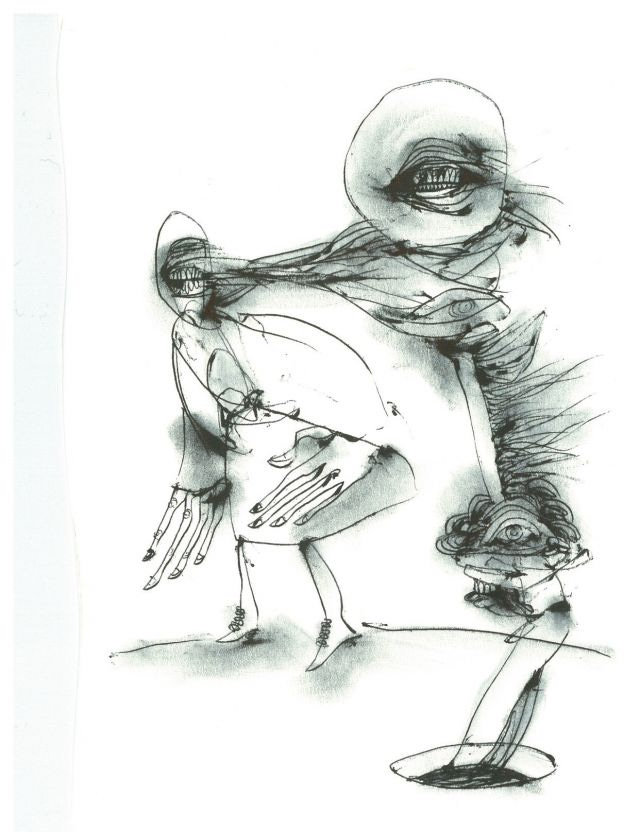

I personally like being thrown in as the caveman sometimes. I think 1970’s science fiction art did the best job of addressing this, and it correlates with my favorites from that era. In all of these images, the abstraction doesn’t lie as much in the composition but the content.

We will never, ever stop arguing about cult teen films

Judy Berman, The Outline

The thing is, the alchemy of the teen cult movie has precisely nothing to do with quality. When we’re that age, all a film or a book or a TV show has to do to earn a permanent place of honor in our personal canons is tantalize our senses and teach us something, anything, about how people live. While growing up should make us more critical of the things we loved as kids, the cult movies we’re drawn to as teens are so crucial in shaping our attitudes toward art that they can short-circuit those critical faculties for decades afterward.

I'm a Spelunky stan, and this article explains why. If reading it inspires you, the original flavor game is available for free here.

Spelunky mashed up two wildly different genres—and invented a perfect game

Clayton Perdom, The AV Club

It was by trying to come up with something that he’d personally find entertaining that Yu hit upon Spelunky’s singular innovation: fusing the classic, instantly accessible platformer with the relentlessly difficult, arcane genre known as the roguelike.

We’re the Good Guys, Right? On the Marvel movies

Daniel Immerwahr, n + 1

And what are the Avengers avenging, precisely? In the ’60s, when the group was formed, it was clear enough. “Let me spell it out to you! We’re supposed to avenge injustice,” explained Hawkeye in Avengers #18. Yet injustice is a word barely heard in the Marvel movies—only Black Panther explores the theme. The other films are obsessed with a different word: protection.

Summer Movie Preview: 15 Movies We’re Reasonably Sure Will Not Be Terrible

Staff, ScreenCrush

You know about most of the big movies already, because they’re the ones with crazy marketing budgets. (Hey, did you know there’s a Star Wars movie coming out this summer? Well, there is. This one has a very slightly different Millennium Falcon in it!) Plus, most of the blockbusters turn out to be ... what’s the word? Crappy, right. They mostly stink.

Next Week on Maddd Science: The Youths

My latest Patreon post: How John Berkey paints Star Wars