Nuclear Apocalypses

Maddd Science

Nuclear apocalypses: So near, yet so far so good.

I actually never used to enjoy apocalypse narratives because I've found them too depressing, but I think paying attention to the news over the past few years has really warmed me up to enjoying the fictional version more. That seems to be true for a lot of us, judging from HBO's breakout hit Chernobyl miniseries.

That said, I've always loved 60s-80s apocalypse and post-apocalypse art: It's the stunning combination of moody, dire scenes with an often vibrant color palette that does it for me, I think. The retro style and colors add enough emotional distance to dilute the actual horror of an apocalypse into a sense of ennui. Feel free to browse through the apocalypse tag on my Tumblr to see if you have the same reaction.

I just found my new favorite article on apocalypses (hat tip to the Faculty of Horror's recent podcast on The Mist): It's from M. R. Carey, the author of The Girl with All the Gifts.

It tracks the entire history of the genre and makes some fascinating statements ("Just in terms of sheer volume, there has never been a time when apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic stories have been produced in greater profusion and variety than we’re seeing now") while throwing in some wry jokes (I'm very jealous of this delivery: "Until recently those end-of-the-world narratives were mostly the province of religious texts, which having told us how things got going in the first place seemed to feel obliged to wrap up all the plotlines at the end"). Highly recommended reading:

A Brief History of the End of the World

M. R. Carey, Electric Lit

Barring a few nineteenth-century outliers (Mary Shelly gets there first, as usual, with The Last Man in 1826) science fiction doesn’t begin to address itself en masse to the end of the world until the 1960s. The pulps flirted with it, but the few doomsday scenarios were far outweighed by the bright, millennarian visions. Most future Earths from the ‘30s to the ‘50s had tidy little galactic empires with well-manicured lawns. The aliens would get a little frisky from time to time, but there was almost always a Buck Rogers or a Kimball Kinnison to put them firmly in their places.

Here's an interesting article that pairs a rundown of 80s-era nuclear apocalypse film with the downbeat argument that we really could use a lot more of it today.

Watching the End of the World

Stephen Phelan, Boston Review

“The post-Cold War generation knows less about nuclear danger than any other,” Schell told the New York Times in 2000. He drew on the contemporary blockbuster Armageddon (1998) to make his point, a movie that reversed the “normal iconic imagery of nuclear weapons” to repurpose them as drilling equipment, essential tools for saving humanity from the arbitrary hazard of an incoming asteroid. Twenty years on, we have yet to find a good use for all these homemade planet-killers, even as the United States and Russia modernize their arsenals with newfangled hypersonic boost-glide systems, uranium-tipped torpedo drones, and low-yield “tactical” gravity bombs.

And yet we don’t make movies about nuclear war any more.

In early 2018, just days before that false ballistic missile alert in Hawaii, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published an essay to that effect by an eighth-grader named Cassandra Williams. Agitated by a class on the subject at her middle school in Dubuque, Iowa, Williams searched out old films she’d never seen or heard of and found herself “completely stunned” by The Day After, the 1983 television feature that dramatized the results of Russian missiles raining on Middle America. Citing “the unpredictable behavior of North Korea and our current U.S. president”, she identified an urgent need for updated equivalents with upgraded special effects—the better to show her peer group what might yet actually happen.

Finally, here's an interesting look at how the official Chernobyl companion podcast happened. Haven't listened to it yet, but I definitely will.

The Chernobyl Podcast is a compelling behind-the-scenes look at the HBO series

Andrew Liptak, The Verge

Sagal outlines the purpose of the podcast in the opening of the series: where the show came from, how it was produced, and how closely it tracks with real history. In that first episode, Mazin explains that “the one [reason] for me to do this from the jump was the chance to set the record straight about what we do that is very accurate to history, what we do that is a little bit sideways to it, and what we do to compress or change it,” and that as the show is largely about the value of truth, he felt that it was important to cover it in some medium.

Speaking of 80s-era Russian investment opportunities not turning out so well... Stranger Things 3 just came out. (Yes, finishing Chernobyl in the same day I started watching the new Stranger Things made for just as jarring a transition as the one I just wrote.)

Here's a smart version of the age-old "Stranger Things is blinkered by its 80s pop culture goggles" hot take.

Stranger Things 3 cements the show as the YA series of our age. For better and worse.

Emily VanDerWerff, The Verge

The systems that underpinned society itself seemed to be radically changing for the better and the worse in the ’60s. In the ’80s, the social order was firmly established, and it was old and straight and male and white. It was a different time to exist. So when I compare Stranger Things to Forrest Gump, I mean that both works capture how it felt to live through the time period — but instead of retelling a long series of news events, Stranger Things builds on how it felt to be around the first time you saw Back to the Future in theaters (as the characters do in season three’s penultimate episode). The show’s relationship to the movies of the ’80s is basically the same as Forrest Gump’s relationship to major world events (and rock music).

My geek readers of a certain age will no doubt be horrified to learn that I've never heard of the game that was apparently "the most polished computer game made up to its release date of mid-1993," Day of the Tentacle. I'm a baby, folks, it was before my time. Here's an interesting dive into the making of it, with one particularly funny anecdote excerpted here.

Day of the Tentacle

Jimmy Maher, The Digital Antiquarian

The most telling sign in Day of the Tentacle of how far computer gaming had come in a very short time is found on an in-game computer in the present-day mansion. There you’ll find a complete and fully functional version of the original Maniac Mansion in all its blocky, pixelated, bobble-headed glory. This game within a game was inspired by an off-hand comment which Grossman and Schafer had heard Ron Gilbert make during the Monkey Island 2 project: that the entirety of Maniac Mansion had been smaller than some of the individual animation sequences in this, LucasArts’s latest game. Placed in such direct proximity to its progeny, Maniac Mansion did indeed look “downright primitive,” wrote Charles Ardai in his review of Day of the Tentacle. “Only nostalgia or curiosity will permit today’s gamers to suffer through what was once state-of-the-art but is by today’s standards crude.” And yet it had only been six years…

Here's an essay charting one writer's origins amid the same underappreciated retro horror comics that hugely influenced icons like Stephen King and George Romero.

I Was A Teenage (Wannabe) Horror Writer

Michael Gonzales, Crime Reads

I didn’t know it at the time, but the horror books were often used as the jump-off, where many young creators got their start before moving on to bigger books. I spent the next week knocking out plotlines, mostly ripped-off from too many viewings of Chiller Theater and Creature Features, to present at our meeting. Following Cuti’s guide, I also produced a four-page script to present to Levitz. While comics are often thought of as a subgenre to real literature, I learned a lot about pacing, dialogue and foreshadowing as well as sharpening my visual sense.

Folks, this twitter thread on the origins of the lesbian detective in fiction has it all: International scope, gobs of historical context, suggestions for additional research, delightfully dry editorialization. Love it. The author Jess Nevins is working on an "Encyclopedia of Fantastic Victoriana, Second Edition," (which is only available as an ebook because it's a massive 2,200 pages) so is clearly Someone To Watch.

Next Time on Maddd Science: Women in Sci-Fi History

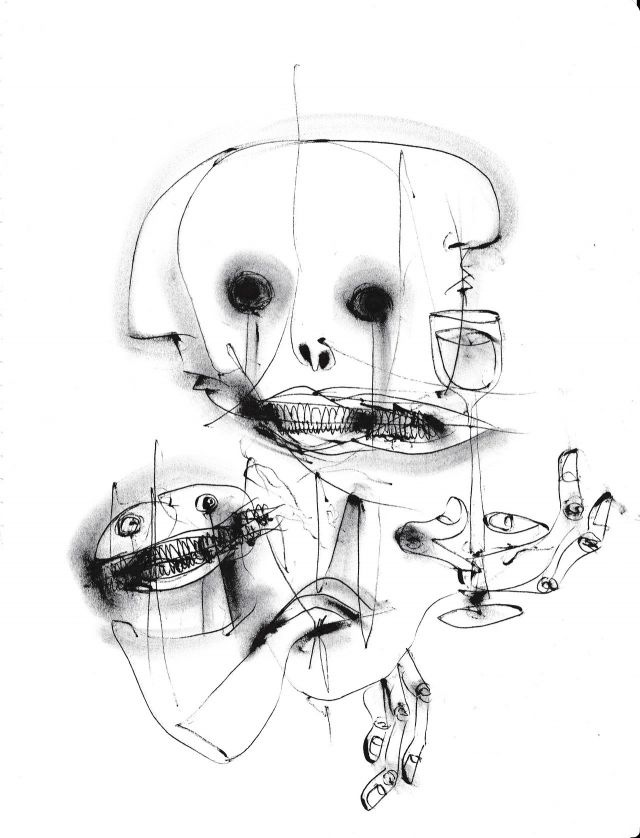

Header image: untitled, by Daniel Williams.

Like this issue? Maybe forward it to someone you think would like it, too. My marketing budget just covers that and my twitter account. And if someone forwarded this to you, you can subscribe here!