Pulp adventure tropes, swipes, and surrealist gambling

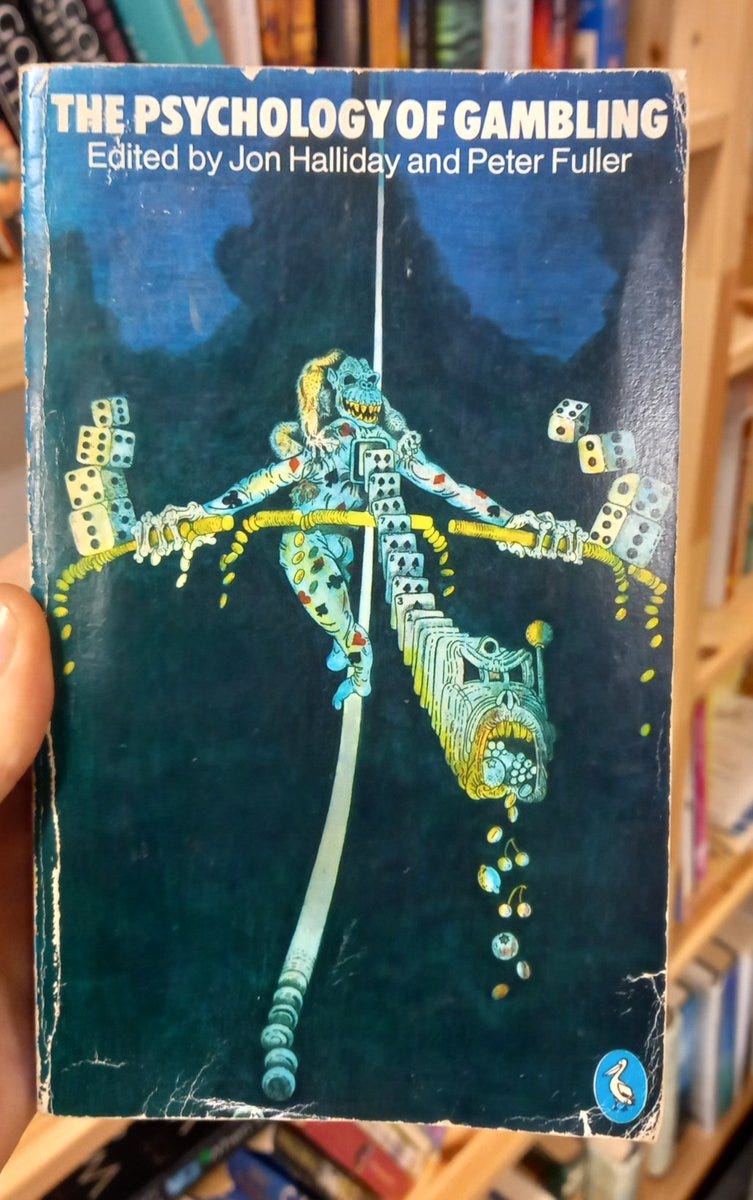

Someone posted a thrift shop find on Twitter a good while back: This absolutely gonzo cover to a 1977 Penguin edition of the nonfiction book The Psychology of Gambling.

I wasn't able to find a clean scan of that cover online, but if any readers know of one, send it my way! It's certainly unique.

The back cover says “Cover design by Alan Aldridge.” I’m a little unclear on the difference, if any, between the cover design and the cover artist, but the art style does seem to fall within Aldridge’s wheelhouse. Here’s a web page about Aldridge that I found while researching that cover:

Science friction

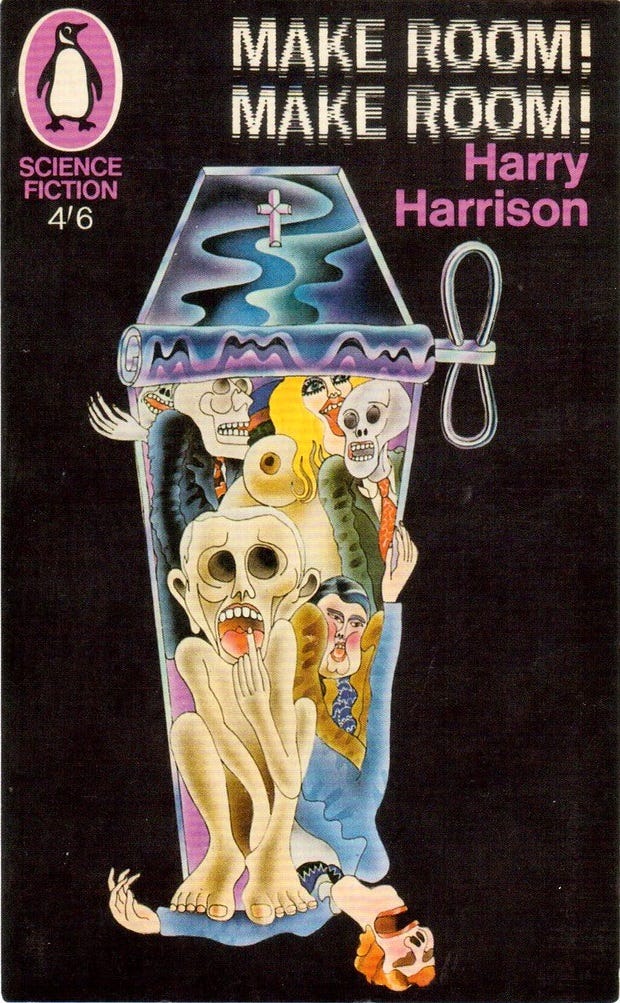

Penguin SF, James Pardey

Penguin sf had never seen anything like it. Aldridge clothed his cast of characters in dicky bows and polkerdots or kipper ties and pantaloons, mixing vaudeville with freak show in a crazy raving medley of surrealism and psychedelia that pinched from Pop Art and flirted with Art Deco. His phantasmagoria of floating images took sf to the brink and the titles of the books said as much. Strung out in shrieking white capitals, they splintered the blackness like a banshee's wail.

***

I continue to be obsessed with the treasure hunting adventure genre and its tenuous connection to real-life archeology. This article takes a pretty strong stance against the genre, but I feel like the issues it discusses could be addressed if adventure writers all started their process with some vigorous research and considered the meta implications of who they’re centering the story on.

Booty calls: Hollywood’s problem with lost-treasure yarns

Steve Rose, The Guardian

Rather than actual history, though, the real origins of this genre lie in movie history, and in particular, that Magellan of archaeological adventuring, Indiana Jones. As notes from a 1981 brainstorming session between George Lucas, Steven Spielberg and Lawrence Kasdan revealed, they were chiefly inspired by the movies they grew up on, such as King Kong, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre and the thrilling Republic serials of the 1940s and 50s. Also mentioned are Ripley’s Believe It Or Not, Disneyland rides and pseudoscientific books such as Erich von Daniken’s Chariots of the Gods. “I don’t think they even knew the name of a single real-life historical archaeologist,” says Justin Jacobs, history professor at American University and author of Indiana Jones in History. “It’s all recycling of previous pop culture. There’s zero historical research in there.”

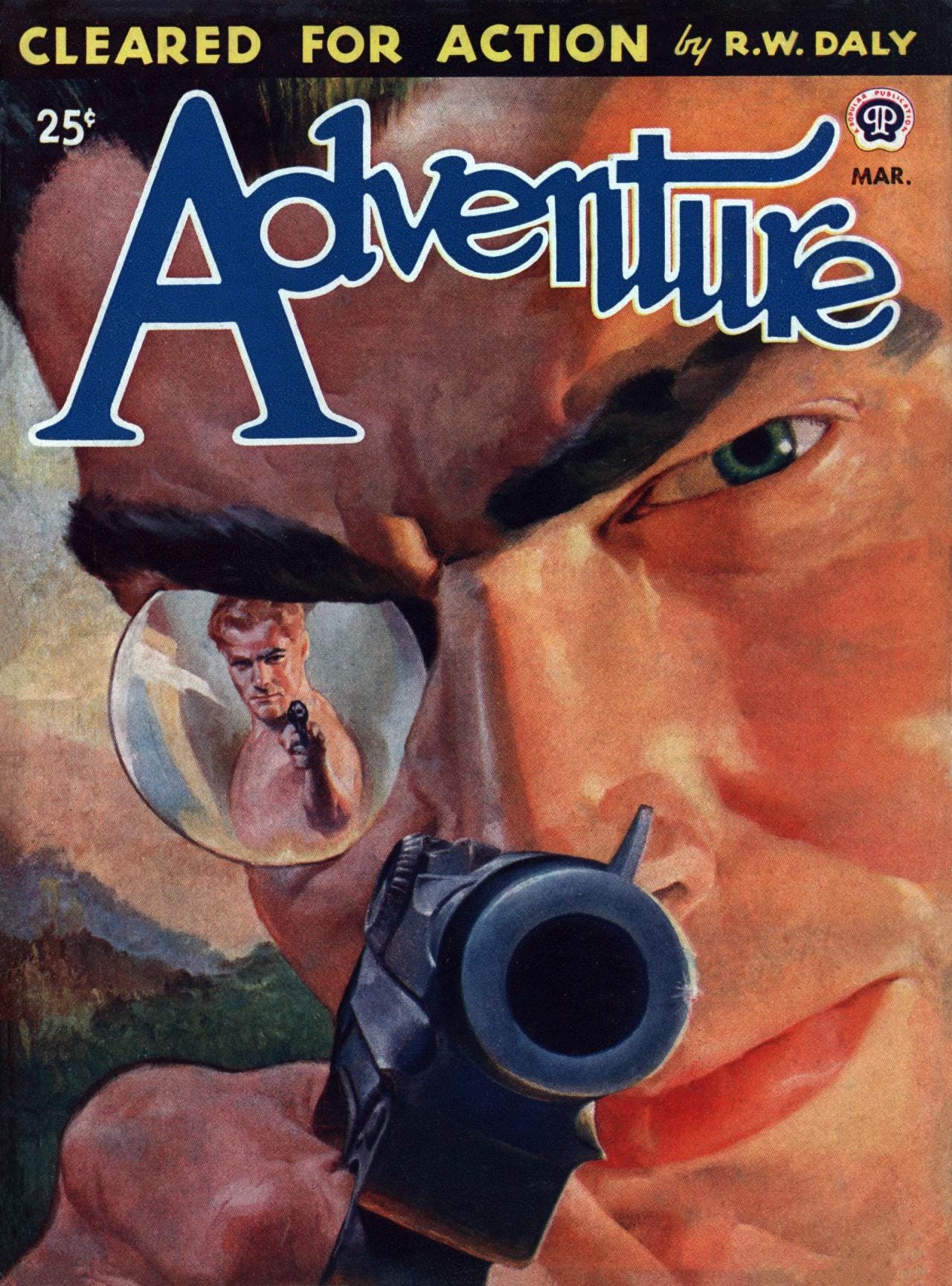

Speaking of pulp adventure stories, I’m getting ever closer to fleshing out a theory that a lot of 60s-80s sci-fi visual tropes were nothing but slightly updated versions of 20s-50s adventure pulp visual tropes.

For evidence of this, I already had the fact that a lot of “skeleton in spacesuit” sci-fi covers feature the desert, mirroring adventure pulp stories of vultures attacking a parched hero in a western. But the “reflection in a space helmet” trope might also have a pulp ancestor, if Griffith Foxley’s March 1946 cover art for Adventure magazine is any indicator:

That said, this connection might not be much deeper than the fact that all artists love cool reflections.

***

Here’s a blistering article on the limits of technology-centric optimism in science fiction:

The Writing On The Wall: Sci-Fi’s Empty Techno-Optimism

Eli Horowitz, Blood Knife

Over and over again, Stephenson and his colleagues tried to skirt or obscure human malfeasance. Worried about the oceans? Just “replant” sea life without stopping to wonder why it died out in the first place! Concerned about ecosystems the world over? Don’t bother to grapple with the reasons why they’re threatened, just carve out a few exceptions for tourists!

That article pairs well with this next one, because it takes a look at how science fiction can more closely address one specific shift in how we live.

Here are a couple quotes from this next article; I couldn’t pick just one. The sheer number of examples Liptak packs into this article was what really drove home for me how large climate change looms in sci-fi and our collective consciousness.

Pop culture can no longer ignore our climate reality

Andrew Liptak, Grist

“The climate disaster is going to become less and less ignorable in the very near future,” says Premee Mohamed, a speculative fiction author and biologist who focuses on reclamation and remediation policy in Alberta, Canada. Her recent novella The Annual Migration of Clouds is set in a post-post-apocalyptic world that’s been heavily impacted by rising global temperatures. “If people choose not to include it in their contemporary realism novels, as time goes on they’re going to be more and more unrealistic.”

[…]

As the modern environmental movement gained steam, John Christopher examined societal collapse after the arrival of a new ice age in his 1962 novel The World in Winter. In the same year, J.G. Ballard’s The Drowned World examined a London flooded by rising sea levels. And of course, Frank Herbert’s landmark 1965 novel Dune placed environmental considerations front and center, brought on in no small part by his concerns about ecological collapse and our treatment of Earth.

***

Found a new search engine that’s geared towards text-heavy websites with fewer modern elements, so basically the anti-SEO search engine: search.marginalia.nu

***

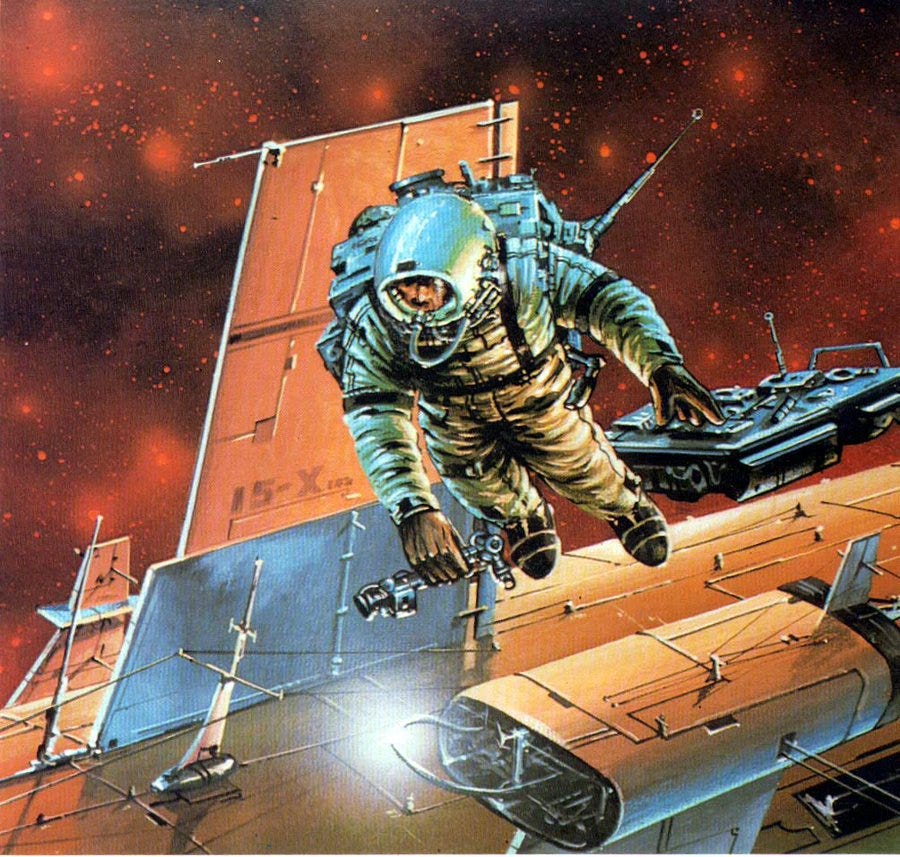

Another entry in the category of Eddie Jones swipes: Here’s an illustration by Jones for Steward Cowley's Space Warriors, a one-off art collection Cowley produced in 1980, outside of his more well-known Terran Trade Authority books.

And here’s a 1972 John Berkey cover illustration for the Star 1 anthology. Pretty similar astronaut there! Right down to the arm band placement.

Thanks again to Winchell Chung for pointing this out to me on Twitter — the other month, Chung pointed out a different Eddies Jones swipe taken from a Berkey cover for a different Star anthology, so Jones is definitely consistent in his inspirations.

***

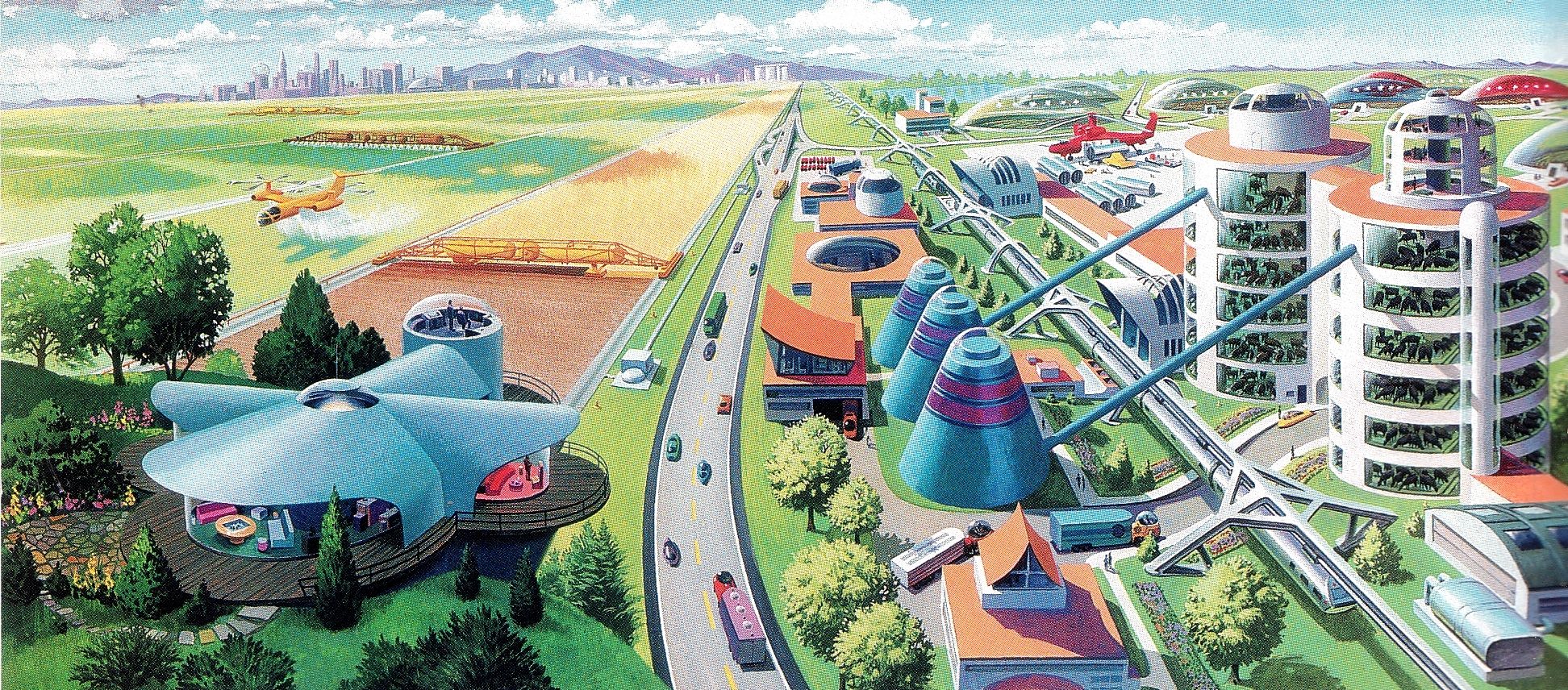

And speaking of swipes, here's another fun one. This is by Davis Meltzer, for National Geographic Magazine's February 1970 issue.

It's a 21st century farm: "Fields stretch like fairways, cattle fatten in high-rise pens, threshed grain flows through pneumatic tubes into storage elevators, and a control tower oversees all."

Then there's this one, a 1974 illustration of the future from Gunther Radtke, titled energieinsel farmfabrik, or "energy farm factory."

This one is technically not a "swipe," since the entire scene has been repainted without directly tracing over the original. Still, a very similar set up here, once you take a close look back and forth!

This one was spotted on Flickr by James Vaughan, who posted the Radtke image. I don't think there's a lesson here, other than that you could get away with a lot of art-swiping shinanigans 50 years ago.

***

Speaking of getting away with things in other countries, here's a fun non-sci-fi thing to end on.

"In 1974 the Romanian Communist Party contacted Peter Falk, known for the titular role in Columbo, to ask him to record a message promoting the series, which was so popular in Romania there were fears that people would take to the streets if it was taken off the air. A bizarre story, pieced together and complemented by a lost-and-found interview with Peter Falk on the subject."

I'd heard that story before, but this 18-minute documentary features easily the most research about the topic, relying on government leaks and footage from a 1995 David Letterman interview that was only available because one fan had recorded all of them.

One last thing: You should also check out this Colombo-themed electronic music, I'm trying to make it the hottest new genre of 2025.