Dunking on Holmes

Maddd Science

Sherlock Holmes is the world's most famous fictional character, and the act of satirizing, spoofing, parodying, and generally mocking him has a long and storied tradition. His first parody was released just four months after the very first Sherlock story saw the light of day, and we haven't let up since.

Which makes sense. Sherlock's whole deal is being superhumanly, hyberbolically, archetypically deductive, and the world he lives in has been generated out of whole cloth to affirm his every thought. Being inhumanly powerful is something he shares with the only other modern mythical figure on par with him, Dracula, and is definitely the main reason he's still popular today. It's also why we really need to constantly take the piss out of him. The best parts of Doyle stories are his flaws, after all: Underestimating women, getting addicted to cocaine, meeting his match in a supervillain who can only be defeated by a slap fight next to a waterfall.

Anyway, I'm glad we've all agreed to mock Holmes mercilessly for the past 130 years, and this is a newsletter dedicated to just that.

First up, the article that inspired me: This incredibly entertaining 'Holmes and Watson' review.

Will Ferrell and John C. Reilly hit career lows in the abysmally unfunny Holmes & Watson

Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, AV Club

We’ve been telling jokes about Sherlock Holmes since the beginning. The earliest send-ups of the world’s greatest detective appeared not long after Arthur Conan Doyle started publishing his stories about Holmes and his trusty sidekick, Dr. John Watson, in The Strand Magazine, and by the early decades of the 20th century, the comic strips and humor sections of newspapers and magazines on both sides of the Atlantic were swarming with Picklocks, Shamrocks, Herlocks, and Shylocks. In all likelihood, “Elementary, my dear Watson,” that most apocryphal of catchphrases, started out in a joke; it never appeared in any of Doyle’s stories, nor in the original version of the hit stage play that first gave Holmes his deerstalker hat and calabash pipe. Mark Twain wrote parodies of the Holmes mysteries, as did O. Henry and P.G. Wodehouse. The Sherlock joke is one of our older pop culture institutions, like Holmes himself.

This is especially true when it comes to film, where depictions of Sherlock Holmes are said to outnumber those of Jesus Christ and Count Dracula. In fact, the earliest Holmes films are parodies, predating any official adaptations of the Doyle stories—the best of which have always had a good sense of humor. But if there are any new jokes left to tell about Holmes, they’re nowhere to be found in the abysmal Holmes & Watson, which might be the worst feature-length film ever made about the “consulting detective” from Baker Street.

Here's a paragraph on Holmes pastiches taken from a larger, interesting article centered on Holmes' cocaine addiction. Fun fact: 1974's “The Seven Percent Solution,” which asserts Holmes' deluded crusade against an innocent Moriarty was due to cocaine addiction, was based on a 1968 professional article from a historian of drug policy who then tried to sue the novelist for stealing his idea. A lot of drama from the Holmes pastiche community.

How Sherlock Holmes Became a Cocaine Addict

Noa Manheim, Harretz

It seems that the figure of Holmes has long since transcended the literary and creative realm to the point where he is no longer merely a fictional character, but practically one of flesh and blood. Numerous writers have attempted either to extend or imitate Doyle’s project. The first parody was written during Holmes’ “life,” only a mere four months after publication of the first story relating his exploits. One of many Holmes scholars, Leslie Klinger, points out that the Holmes bibliography completed in 1995 mentioned more than 2,000 sequels and pastiches of his adventures.

Here's a section in the Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia dedicated to pastiches and parodies, notable mostly because it lists all the soundalike names the parodies used: Sherlaw Kombs & Whatson; Chubblock Homes; Picklock Holes & Potson; Thinlock Bones & Whatsoname; and one bizarre 1901 entry that just uses "Sherlock Holmes" as normal but then goes ahead and makes his sidekick "Wablins."

This sounds like one of the better ones:

The Incredible Schlock Homes, by Robert L. Fish: Book Review

Marilyn Brooks, Marilyn's Mystery Reads

In “The Adventure of the Adam Bomb,” Homes arranges a fake funeral for himself because his disappearance is essential to solve a crime. When his colleague Watney questions the amazing disguise Homes needs to wear while presumably dead and yet be able to investigate, Homes explains. The body in the casket? “An excellent example of Madam Tussand’s art.” The “corpse’s” extra weight? “One of Mrs. Essex’s pillows.” His present stature, at least a foot shorter than Homes’ actual height? “Special shoes,” responds the detective. Are you beginning to get the idea?

Doyle himself wasn't above mocking his creation, though this short story isn't making fun of Sherlock so much as making fun of how quickly the Holmes universe turns against anyone else who tries to do exactly what Sherlock does all the time. It's practically flash fiction, so you'll breeze through it.

How Watson Learned the Trick

Arthur Conan Doyle, via the Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia

"Your methods," said Watson severely, "are really easily acquired."

"No doubt," Holmes answered with a smile. "Perhaps you will yourself give an example of this method of reasoning."

Finally, one last unrelated article I found this week and thought was cool:

Joe Walker: How the Editor of “Widows” Pulled off the Perfect Heist

Alexander Huls, Frame.io

[Walker] explains,“In terms of the weight you give to every moment in the scene, more often than not you’re going to play one big moment, and give that space, but then some other thing’s going to have to snap past quickly.” In other words, to create room for one scene to breathe more, you have to take away room from another scene.

Since Widows is dialogue-heavy for a heist movie, that was an especially important task for McQueen and his editor. Sometimes to buy space for more dialogue in one scene, they had to entirely remove dialogue in another scene. For example, there’s a scene near the end of the film between Belle (Cynthia Erivo) and Veronica (Viola Davis) in a car. In an earlier cut, they had a long conversation, but because the next scene also required extensive dialogue, McQueen and Walker thought, “‘Could we play this scene as a series of looks and have it wordless?’ That worked so perfectly,” says Walker.

Next Time on Maddd Science: 70s-era Bigfoot

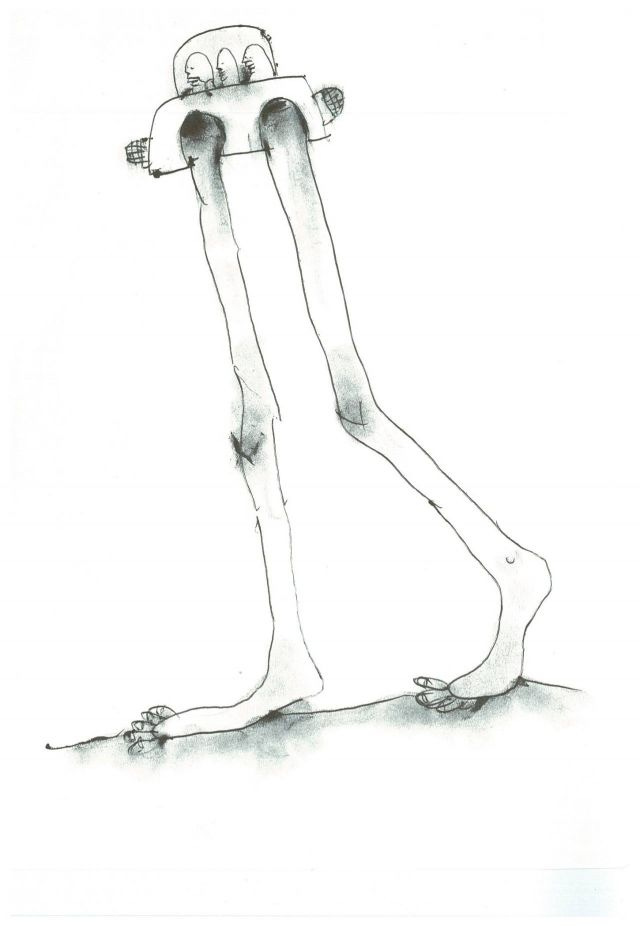

Header image: “untitled,” by Daniel Williams.

Like this issue? Maybe forward it to someone you think would like it, too. My marketing budget just covers that and my twitter account. And if someone forwarded this to you, you can subscribe here!