Book Notes: 'Mass - The Art of John Harris'

“I can only work in a chaotic, fluid, rambling fashion. It’s the way I am.” Wow, mood

Mass - The Art of John Harris, written by Ron Tiner, came out in 2000 in the UK from Paper Tiger. It definitely works as a character portrait of the artist, although it was a little light on artistic analysis.

I have a terrible habit of confusing John Berkey and John Harris, partially because of those first names, and partially because they both have similar styles: Impressionist spaceships.

So, while reading this book, I was interested in the differences between the two. Turns out Harris is 16 years younger, but thanks to Berkey’s decade-plus spent in ads and calendars, Harris entered the book cover market just a few years after Berkey, in 1970, according to page 7 of Mass.

The plot twist I didn’t see coming: Harris did a few bad covers and then took five years off to study Transcendental Meditation from 1972-77. He credits this time for enabling him “to pick up the imagery that was in him,” Tiner says, images that Harris says “just wouldn’t leave me alone, and they remain the major impetus and motivation behind my work.” Harris’ main career kicked off around 1979, and is still going strong today.

Page 13: Harris got his start by joining London’s Young Artists agency. His first gig was three paintings for 1979’s Alien Landscapes, depicting James Blish’s Okie Cities.

Page 20: Earlier, Harris had wanted to join the Royal Air Force. Then the physics master at his school died, and wasn’t replaced.

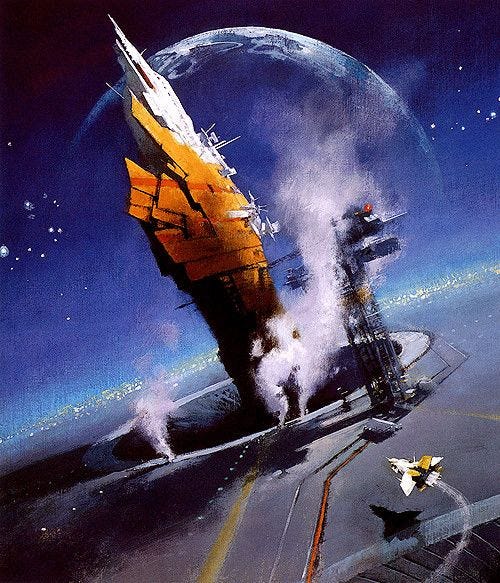

Page 24: Harris’ paintings try to evoke emotions and themes. This one, an early ink painting for Frederik Pohl’s Drunkard’s Walk, attempts to “induce a sense of vertigo” — pretty effectively, in my opinion.

Page 25: This one, Waiting for Clearance, has a theme of departure. “The image of vapours rising from idling engines creates the feeling of anticipation,” Tiner says.

Page 33: The two threads of Harris’ artistic ambitions: Astronomy/space travel, and landscape painting.

Also 33: He studied Fine Art in college, not Illustration

Page 34: Harris tends to vividly imagine the fictional locations he depicts. Like, really vividly. Of one non-sci-fi image of the Andes, he says, “This one’s looking east in the late afternoon, but don’t ask me how I know.”

Page 46: “I can only work in a chaotic, fluid, rambling fashion. It’s the way I am.” Wow, same.

Also page 46: Harris seems to like crowds on steps as a motif.

Harris graduated with “a very medicore pass” (p 46) and a lot of debt, “his parents having declined to finance him through his art studies” (p 55). Feels like there’s a story there!

Page 58: Harris had a series of visions, “genuine visionary experiences,” that became the basis for his 25-image series, the Mass pictures — a “loose collection of images that are connected by the common themes of vastness (in both time and space) and of possible futures for mankind.”

Completed between 1978 and 1979, though many have since been repainted.

The visions were as varied as “standing in a desert watching the rotation of the Andromeda Galaxy” (despite the rotation taking two thousand million years or so), and standing in the playing fields of his old school and looking up to see the Moon falling toward the Earth.

One of the images was the one used for the operating manual cover for the Sinclair ZX81 computer.

Like Robert McCall, Harris painted a few works in which “gravity-free engineering” had been invented in the future. It’s because flying cities look cool (citation needed).

Page 76: “The main reason people respond so readily to his work is, he thinks, because humankind’s view of ourselves and our place in creation has undergone a profound change in the last few decades, largely because of one single achievement: the emotional climax of the Apollo 11 Moon mission of 1969”

Page 81-85: NASA invited Harris to see a launch of the Discovery in 1985 as part of a program to get artists to document NASA’s work. Harris was the first British artist comissioned by NASA. Harris made an unusual choice that the Mass book doesn’t really dwell on: He painted the empty, smoke-swept launchpad 60 seconds after the shuttle had left it. It’s a more wistful, meditative vision of NASA than you’ll see from, say, Robert McCall, who worked with the same NASA program.

By the time Houston’s staff saw the finished piece, the next launch had gone horribly wrong — the Space Shuttle Challenger had exploded in January 1986. In this unexpected context, the Harris painting gained a “funereal ambience,” and the work still hangs in the Kennedy Center.

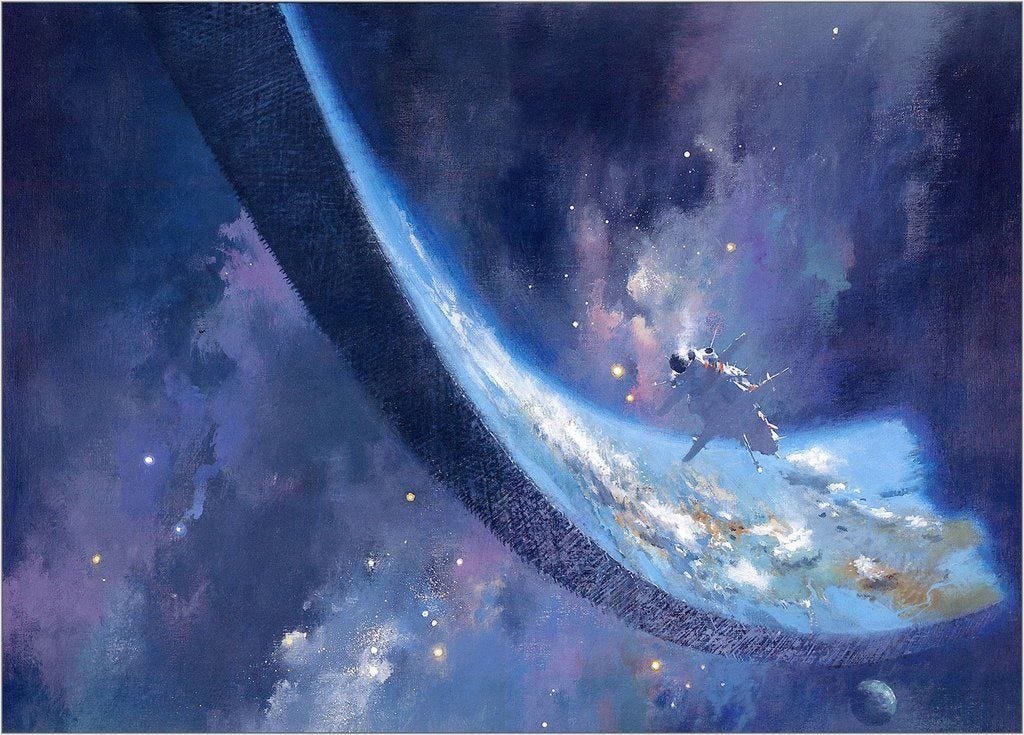

Page 85: John Harris’ pastel 1996 cover to The Ringworld Throne intentionally shows Ringworld while still under mega-construction in order to make it easier to fit into the painting.

Page 88: Harris found that too much commerical work could easily dilute his vision, turning it into generic science fiction illustrations, Tiner says. Harris: “The moment that started to happen, I lost something essential to the imagery. And it was only when I was free of commercial and economic restraints that I could produce any images that related to the magic.”

Harris has another image series, Fire, with a theme of the “human, individual, personal scale,” centered on a city built inside a volcano.

Harris has painted the Nazca Lines of Peru as well as a crystal version of Stonehenge — he’s drawn to unanswered questions from history.

Page 104: Another Harris motif: Projecting planes.

***

Plus, here are a couple interesting Harris works here that I couldn’t resist tweeting about as soon as I heard about them:

Next Time: Even more Harris, with notes on 2014’s The Art of John Harris: Beyond the Horizon. Technically, these are the notes I promised last time, but I realized I had both of Harris’s art books, so I read them in chronological order.