Black Panther

Maddd Science

Back in late 2015, I found an interesting Wikipedia sub-section about the Comics Code Authority. It's an organization created in response to a 50's-era comic book moral panic: It policed any comic book hoping to make it to the (industry-sustaining) grocery store shelf, checking for such evils as plunging necklines and the word "horror" on covers. It was also run by racists, as demonstrated by a 1956 incident in which the CCA rejected a sci-fi story due to "the central character being black."

That incident serves as a microcosm of the systemic barriers that kept afrofuturism from breaking into the mainstream. It's also the same environment in which the Black Panther first emerged, and back in 2015 I figured it would make a great article. Two and half years and several completely new drafts later, I still haven't cracked it, and I've had to admit that a white guy like me might not have the perspective needed to tell an illuminating history of afrofuturism. I even interviewed Ta-Nehisi Coates for the sucker, too, in a ten-minute phone call right as he was starting work on issue 12 of his Black Panther run.

The Atlantic and the Pacific Standard looked at drafts and then passed back in 2016, and since I mothballed the article until after Black Panther debuted last week, it's not as timely (I mean, even the NYT has discovered afrofuturism). It's in limbo for now: Does my lack of perspective make it *cough* unrevisable? It might! But it also has a lot of good stuff in it that might just need to find its center.

Until then, I guess I'm just humblebragging that I have access to a Coates interview that no one else on earth has read.

Anyway, here are some Black Panther takes:

Fear of a Black Universe

Kaila Philo, The Baffler

The point of Afrofuturism, like science fiction in general, is to open the racial imagination and to re-thread our social fabric—to help create a society removed from our own, perhaps as a form of escapism. Black Panther attempted as much, but this is a feat that will require more than one film—it may require a universe.

How Black Panther Asks Us to Examine Who We Are To One Another

Rahawa Haile, Longreads

In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, Black Panther spent its opening weekend sold out five times a day out of a possible five showings. A question I repeatedly found myself asking is where Africans watching this film fit within the Afrofuturist possibility of Wakanda? How do you watch the dream of Africa, set within the real Africa, created by filmmakers in the diaspora, and then emerge to martial law?

Dreams of Africa: The Fantasy Politics of "Black Panther"

Matt Zoller Seitz, RogerEbert.com

Coogler's movie builds such a distinctive self-contained universe that it's a shame to think of the characters being reduced to fringe players in a Marvel yearbook-photo-in-motion, delivering between 10 and 40 expository lines each when they aren't punching people in the face. Whether you see T'Challa's story as a disappointing confirmation of this franchise's limitations or a refreshing indication of how flexible it can be will depend on what you expect from superhero movies as a genre, and from profit-driven American popular culture generally.

Fascinating article on how W. E. B. Du Bois' love of pulp fiction has been flattened away from his canonical image:

W. E. B. Du Bois, Aesthetics, and the Weird

Britt Rusert, AAIHS

Beyond its illumination of the popular and even pulpy dimensions of Du Bois’s essays and academic studies, we follow Mark Jerng’s recent argument that, far from being a marginal body of literature, pulp fiction was itself central to cultural forms of “racial worldmaking” beginning in the early twentieth century. The “weird” is a particularly helpful category for thinking about Du Bois’s short stories. Most commonly associated with the early-century writings of H. P. Lovecraft, weird fiction traverses and mixes science fiction, horror, the gothic, mystery, and colonial adventure in order to make the real feel disorienting, uncanny, and often horrifying.

If Fiction Teaches Us Anything, It's To Never Underestimate Teenagers Discovering Their Powers

Thu-Huong Ha, Quartzy

Fiction is littered with brainy kids who see clearly where fumbling, unimaginative adults can’t: Encyclopedia Brown, Nancy Drew, even the mystery-busting gang surrounding Scooby Doo. In the Hunger Games series, adults and authority figures are more than incompetent; they are easily corrupted and will resort to their own violent agendas every time.

I think slow character development is a big casualty of those "premium" TV shows designed to be huge events. They instead tend to rely on easily guessed plot twists, as both Westworld and Star Trek: Discovery have proven. But the Starz show Counterpart is the antidote.

Getting Two Versions of J.K. Simmons Is the Best Reason To Watch Counterpart

Eric Thurm, Esquire

Surrounded by shows that are competing for audience eyeballs in the era of Peak TV, the restraint of Counterpart, especially given its potentially outsized, ridiculous premise, is impressive. In fact, it mirrors Simmons’ performance—by far the best reason to watch the show.

Great article that I totally agree with on the sexual politics of Fifty Shades of Grey. I'd be interested in hearing how large a problem this is with other online romance/erotica, given those genres are such a huge part of the Kindle industrial system.

Fifty Shades and the secret compromises of women

Lili Loofbourow, The Week

The fact is, people lie about sex all the time: not always on purpose, and not always for themselves. Many say, for example, that they wanted to give what was taken from them. Why? Because it produces an acceptable story of the self and the relationship. To have had something done to you (like sex, or abuse) without your wanting it? This, in our culture, makes you a victim. It makes your partner a monster. Easier to say you wanted it and convince yourself it's true.

Now imagine doing this and liking it. That's Fifty Shades of Grey.

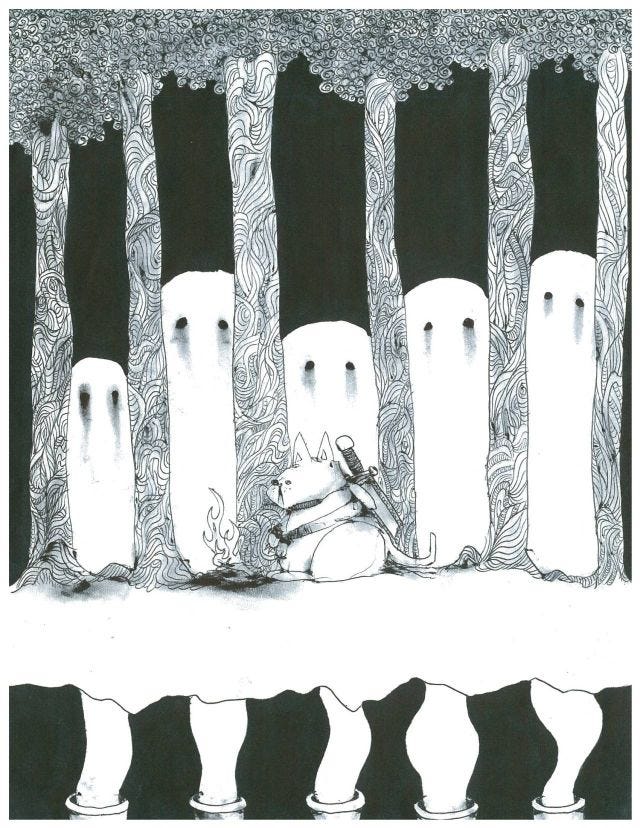

Next Week on Maddd Science: Dope Rider