Why “Show, don’t tell” is dumb

Maddd Science

I'm starting out with two articles about why the most quintessential writing advice of fifth-grade English teachers everywhere isn't all it's cracked up to be. Because why tell you when I can show you much more eloquent people telling you?

Viet Thanh Nguyen Reveals How Writers' Workshops Can Be Hostile

Viet Thanh Nguyen, New York Times

Reacting against the rising proletarianism of American writing before World War II and the specter of Soviet power, American writer-teachers promoted the idea of creative writing as a defense of the individual and his humanistic expression. Politics and the spirit of collectives would not be in fashion. What would be in fashion: voice, experience, and showing rather than telling.

Stranger Things, BoJack Horseman, and the weird power of telling, not showing

Todd VanDerWerff, Vox

Of all of the ways Stranger Things apes the ’80s popcorn movies that inspired it, its willingness to simply come right out and state its moral — the ethical code its characters live by — might be one of the least heralded.

Coincidentally, I have another Stranger Things-related piece to run here, too:

‘Stranger Things’ and the Limits of the Netflix Model

Ciara Wardlow, Film School Rejects

Netflix has been primarily responsible for turning binging into more or less the default television-watching strategy. It’s arguably their signature thing. While their “season dump” model for releasing Netflix original series has certain advantages, the next Game of Thrones will never be released in this way, regardless of the quality of the content, for three reasons: duration, suspense, and synchronicity. These three things are key to the development of a bona fide cultural phenomenon, and the Netflix model undermines all of them.

Here's a fascinating article about the nineteenth century's version of superhero movies:

Literature’s Arctic Obsession

Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker

Writing in 1853 in Household Words, the popular weekly magazine edited by Charles Dickens, the journalist Henry Morley opined, “There are no tales of risk and enterprise in which we English, men, women, and children, old and young, rich and poor, become interested so completely, as in the tales that come from the North Pole.”

I looked up the fan theory about Sherlock Holmes secretly being Professor Moriarty the other day and was surprised to learn that it originated with PG Wodehouse. Here's a succinct collection of the humor writer's thoughts on Arthur Conan Doyle.

Wodehouse on Conan Doyle

Some unnamed Wordpress blogger in 2013

I have noted before, while reading Right Ho, Jeeves, how much it draws from and parodies the Sherlock Holmes stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. In fact, the whole book can be read as if Bertie Wooster is Sherlock Holmes, or at least that he imagines himself to be. Rereading it this way threw up a surprising number of examples, all the way from obvious ones like “You know my methods, Jeeves. Apply them.”, to references so subtle that it’s not clear whether Wodehouse is consciously parodying Sherlock Holmes, or it’s a simple case of one author influencing another.

And that's it! Work got in the way this week, so this issue's shorter than normal, but I might have a longer issue next time to make up for it.

Next Week, on Maddd Science: Christmas

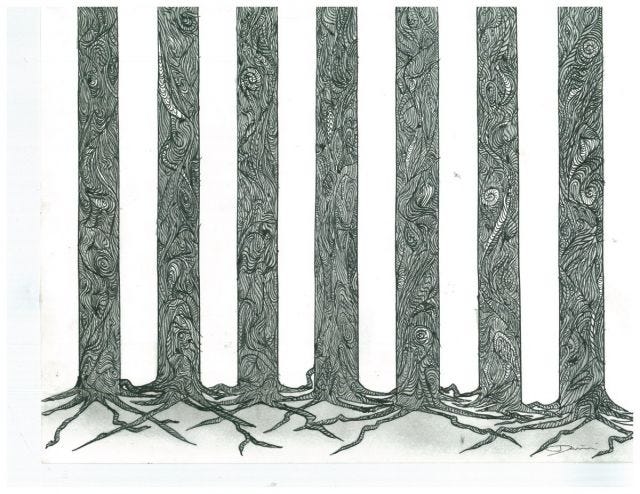

Header image: untitled, by Daniel Williams.