Stranger Things

Maddd Science

As a fan of examining the structures that stories rely on, I love meta narratives like Stranger Things. Stranger Things isn't set in the 80s. It's set in a movie-80s that never existed. Granted, that approach has plenty of flaws, but I try to judge a show on its own standards, and Stranger Things has aggressively established its particular pastiche-y blend.

That said, and maybe this is just me, but it feels like the internet's hot take machine hasn't powered up to nearly the same levels as it did for season one. Or maybe I'm calling it too soon. But I did find a few angles that I enjoyed.

Something out of science-fiction: A short history of Dragon’s Lair

Simone de Rochefort, Polygon

One of the very first hand-drawn video games has a stellar pedigree, and a startlingly long life, despite the fact that most people agree it’s not actually fun to play.

Stranger Things 3 should go all in on the trilogy thing

Clayton Purdom, The AV Club

What started as a narrow but rich homage to a specific set of cultural touchstones has the capacity to morph into a richer, more fun examination of filmic convention. They’ve said they’d like to wrap the whole series up in four or five seasons, but that sets them up for a bit of a predicament, in that films think in triplicate. There is a rich history of philosophizing about the structure of these broad popcorn trilogies.

How ‘Stranger Things’ Star Millie Bobby Brown Made Eleven ‘Iconic’ and Catapulted Into Pop Culture

Debra Birnbaum, Variety

Brown, now just 13, has never trained professionally as an actor. Never gone to acting school. Never taken a class. She simply decided at age 8 she wanted to be on-screen, and her parents obliged, moving her and her siblings from Bournemouth in England to Orlando, Fla., to allow her to pursue her dream.

Stranger Things doesn't appeal to some for the same reason it appeals to me: It substitutes movie logic for the real kind. With that in mind, here's a deeper examination of verisimilitude in fiction centered on a topic that I have personally verified can power a dinner party conversation for almost too long.

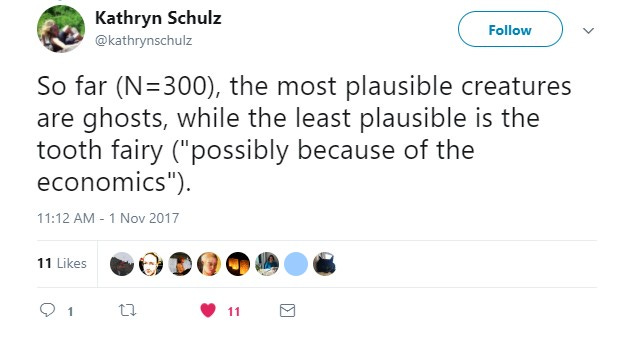

Fantastic Beasts and How to Rank Them

Kathryn Schulz, The New Yorker

Never mind, for now, whether or not you actually believe in any of these creatures. We are interested here not in whether they are real but in to what extent they seem as if they could be. Your job, accordingly, is to rank them in order of plausibility, from most likely (No. 1) to least likely (No. 20). Better still, if you are in the mood for a party game this Halloween season, try having a lot of people rank them collectively. I guarantee that this will produce a surprising amount of concord—who among us could rank the tooth fairy above the Leviathan?—as well as a huge amount of impassioned disagreement. The Loch Ness monster will turn out to have a Johnnie Cochran-level defense attorney. Good friends of yours will say withering things about mermaids.

Also, you can rank those 20 impossible creatures by plausibility in an actual academic survey that Kathryn tweeted about. The best tweet in that thread:

I Love Spoilers

Matt Domino, The Outline

When I spoke to professor Christenfeld, he told me about a colleague who is a big sports fan but never watches the games in real time. “He records sports games because he can’t stand the anxiety of whether his team won or lost,” Christenfeld said. “He’ll go back and watch them after he knows the result.”

When Popular Fiction Isn’t Popular: Genre, Literary, and the Myths of Popularity

By Lincoln Michael for Electric Literature

There is an odd cognitive dissonance that happens in these conversations, where we are simultaneously supposed to believe that literary fiction is ‘mainstream fiction’ and genre fiction is ‘ghettoized,’ and also that literary fiction is a niche nobody reads while genre authors laugh all the way to the bank. Throw into the mix a recent Wall Street Journal article on the increasingly practice of giving million dollar advances to literary debut novels, and you can see that the truth of the matter is pretty unclear.

Here's an article on the best part of the new Thor movie: Its weirdo director.

Get to know the films of Taika Waititi, the brilliantly funny director of Thor: Ragnarok

Alissa Wilkinson, Vox

Waititi’s four feature films vary in scope and subject matter, but they share some uniting factors that have garnered him a devoted set of fans: an interest in underdogs and outsiders, and a self-referential comedic sense that never gets in the way of real feeling.

The cardinal rule of plot twists: Don't knock down anything you haven't set up. And yet un-foreshadowed shocking swerves can still support an 8-film franchise, as unpacked by this blithely detailed explanation of the "gob-smackingly illogical" Saw series.

Watching the 'Jigsaw' Twist Unfold Is an Existential Experience

Simon Abrams, The Hollywood Reporter

These movies are obsessed with the notion of impartial justice, but they themselves never play fair with viewers. [...] The Saw movies are wildly inconsistent in most every other regard, but they are alike in one respect: none of them abide by the rules that they profess to care so much about.

Video: References to 70-80’s movies in Stranger Things

Next week: Franchise Evolution

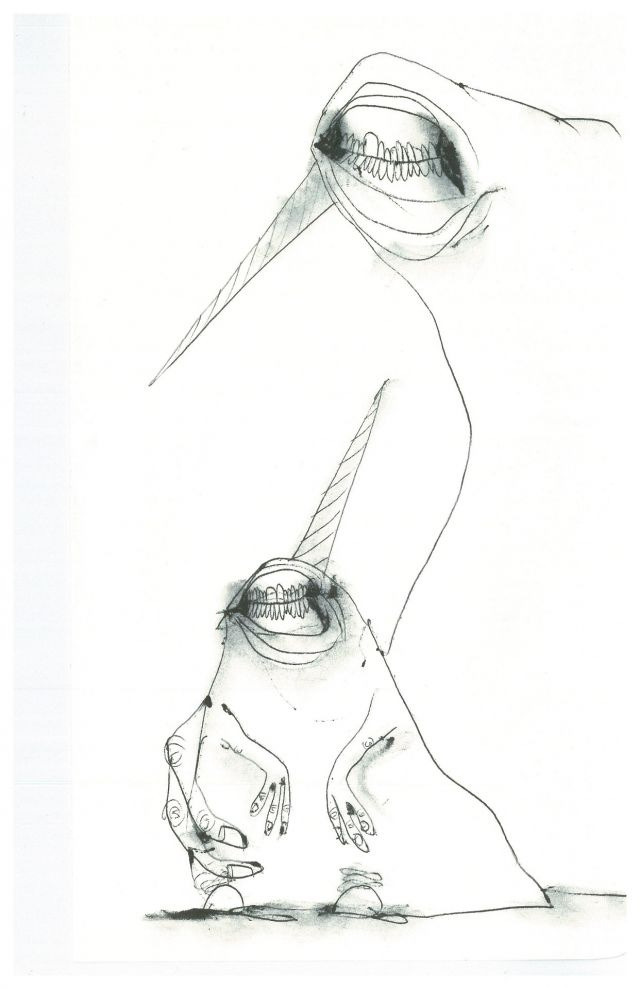

Header image: "first day of school on Ar-nool-7" by Daniel Williams