Indiana Jones

Note: This issue comes with a trigger warning for rape. Nothing graphic, but it's a little blunt, so if you don't want that in your life today, you might consider bailing out now. Thanks.

Maddd Science

When it comes to fictional characters that really deserve their own #MeToo retrospective, Indiana Jones has got to be near the top of the list.

You probably think you know why! It's that whole scene in Raiders where Marion heavily implies he statuatorily raped her, and then Indy victim-blames her in response (The exact dialogue: "I was a child! I was in love! It was wrong and you knew it!" "You knew what you were doing").

Sure, if you squint, you can make this less creepy. Maybe she was 18 or something, and she's using "child" real loosely. Once you look into the filmmakers' on-record thoughts on the matter, though, things get a lot worse. There's a transcript online of the audio from a meeting between George Lucas, Steven Spielberg, and Larry Kasdan where they hashed out the concept. It has a ton of interesting details in it, but here's the creepy bit, where they're discussing Indiana and the character who eventually became Marion:

G — We have to get them cemented into a very strong relationship. A bond.

L — I like it if they already had a relationship at one point. Because then you don't have to build it.

G — I was thinking that this old guy could have been his mentor. He could have known this little girl when she was just a kid. Had an affair with her when she was eleven.

L — And he was forty-two.

G — He hasn't seen her in twelve years. Now she's twenty-two. It's a real strange relationship.

S — She had better be older than twenty-two.

G — He's thirty-five, and he knew her ten years ago when he was twenty-five and she was only twelve.

G — It would be amusing to make her slightly young at the time.

S — And promiscuous. She came onto him.

G — Fifteen is right on the edge. I know it's an outrageous idea, but it is interesting. Once she's sixteen or seventeen it's not interesting anymore. But if she was fifteen and he was twenty-five and they actually had an affair the last time they met. And she was madly in love with him and he...

S — She has pictures of him.

G — There would be a picture on the mantle of her, her father, and him. She was madly in love with him at the time and he left her because obviously it wouldn't work out. Now she's twenty-five and she's been living in Nepal since she was eighteen. It's not only that they like each other, it's a very bizarre thing, it puts a whole new perspective on this whole thing. It gives you lots of stuff to play off of between them. Maybe she still likes him. It's something he'd rather forget about and not have come up again. This gives her a lot of ammunition to fight with.

S — In a way, she could say, "You've made me this hard."

G — This is a resource that you can either mine or not. It's not as blatant as we're talking about. You don't think about it that much. You don't immediately realize how old she was at the time. It would be subtle. She could talk about it. "I was jail bait the last time we were together." She can flaunt it at him, but at the same time she never says, "I was fifteen years old." Even if we don't mention it, when we go to cast the part we're going to end up with a woman who's about twenty-three and a hero who's about thirty-five.

Needless to say, you can go through this exchange and pick out out a new aspect of rape culture in every line. The men here are all reinterpreting the effects of rape to de-emphasize women's experiences and prioritize men's experiences: Marion's attempt to address years of trauma turn into "ammunition" she can "fight" with, Indy's need to avoid responsibility is softened to "something he'd rather forget about." Meanwhile, Spielberg thinks he has a contribution that can make it a little better: She was "promiscuous," so it was really kinda her fault if you think about it.

The actual actors were 39 and 30 in the film, and Marion mentions that it's been ten years. Still, it's obvious that the filmmakers intended to imply that it was an underage relationship in the film, as a way to give Indy an "interesting" past. And the fact that they immediately considered an 11-year-old/42-year-old relationship is pretty eye-opening.

I'm almost surprised we haven't seen a bigger expose on this, really, given that we're in the age of pop culture analysis and no one's above pointing out other weird quirks of the franchise. Polygon did cover it in 2015, and I expect it'll come up again once Indiana Jones 5 rolls out.

Also — and this is unrelated to anything except the fact that I love Indiana Jones — you folks might want to check out the five-issue Abbott comic series by Saladin Ahmed and Sami Kivelä. It meets a few of my internal criteria for a modern imagining of Indiana Jones: It's set in the 70s, so the time period is 40-ish years earlier, same as Indy, and it stars a black woman, so it avoids Indy's great man theory/colonialism. She's a journalist in Detroit and I would have picked a globe-trotting book archivist, but close enough.

All right, here's the rest of the newsletter, starting with my favorite movie of 2018, Widows.

Let’s Talk About the Ending of Widows

Kevin Lincoln, Vulture

Whatever McQueen’s reasons for choosing this approach — heightening the realism, keeping the focus on the characters, thumbing his nose at expectations — it creates a stranger dynamic than what we’re typically left with at the end of this kind of movie.

Television Learned the Wrong Lessons From The Sopranos

Josephine Livingstone, The New Republic

This is the danger of allowing superfans to define the meaning of a television show. Though they may know The Sopranos better than anyone, they may end up taking away the wrong lessons. In the end, neither Paulie’s weird hair nor Tony’s panic attacks represent the core of what was good about The Sopranos. Instead, the show’s pedigree lies in its handling of a few words, here and there—an old man in an armchair denouncing “disharmony.” The joy of watching a Sopranos patriarch comes not only from his easy authority, but also from the language he uses to express it.

Apropos of nothing, if I was a history novelist, I would definitely be researching a story set during one of the last few big eras for con artists. We're in one now, and I think con novels are going to be huge hits for the forseeable future. More info here from a long-time fav of mine, Maria Konnikova:

Why scammers are everywhere now — and why we love them

Rebecca Jennings + Maria Konnikova, Vox

Cons always thrive in moments of transition. All the golden ages of the con throughout history have been during times of social upheaval: the Industrial Revolution, westward expansion and the gold rush, those are some of the big moments where cons completely took off. I think something similar’s happening right now, with not just the technological revolution but the social media revolution. It has really ushered in a new golden age of the con.

I hate getting too negative about emerging storytelling formats, but I have to say I'm bearish about the creative future of Chooseable-Path-Adventure stories like Netflix's Bandersnatch. They seem like a worse version of a video game. Here's an article that dissects the pros and cons, and also doubles as an entry in the "can book publishers get rich off peak TV?" genre.

Books, Games, Film: Choose the Next Path for Storytelling

Porter Anderson, Publishing Perspectives

Kevin Fallon at The Daily Beast worked hard to get onto the fence, writing that the show is “a major accomplishment in storytelling” but also “one of Black Mirror’s lamest outings yet.” And where his appraisal might chill some bookish types who have hoped they might choose the make-more-shows-like-this option from books is in his observation, “It turns out that when television starts to become a video game, the integrity of the story is muddied by the thrill of choice and control.”

I mentioned the Zombi 2 soundtrack a few newsletters ago, and I finally got around to seeing the film the other day (It's free on Walmart's streaming service Vudu). Here's a review that gets into the making of the film, sharing a lot of facts about the grimy world of retro horror ephemera.

Most interesting: The film is an unauthorized "sequel" to George A. Romero’s Dawn of the Dead, released in Italy as Zombi, because "it’s been suggested that Italian copyright law allows anyone to market their film as a sequel to another." The industry kept going after Zombi 2, crafting a ramshackle lineup of unrelated and presumably terrible Zombi sequels all retitled by ripoff artists who are weirdly respectful of each other's work. Zombi 8 didn't need to honor all those other films before it, yet it did. Brings a tear to my eye.

Zombi 2 (1979)

Kevin Lyons, the eofftv review

Other films in the “series” were also just re-titlings of unrelated films. Zombi 4 was used for re-issues of Mattei’s Virus (1980) and After Death (Oltre la morte) (1989) and in Greece Bakterion (1982) also went out under that title. Zombi 5 was Claudio Lattanzi’s Killing Birds: Raptors (1987). In Germany Romero’s Day of the Dead (1985) was released on video as Zombie 2: Das Letzte Kapitel while in the States several films were re-issued by T-Z Video, repackaged as bogus sequels to Fulci’s film: José Luis Merino’s La orgía de los muertos (1973) became Zombie 3: Return of the Zombies; Jesus Franco’s Christina, princesse de l’érotisme (1973) became Zombie 4: A Virgin Among the Living Dead and Revenge in the House of Usher (1983) was re-released as Zombie 5: Revenge in the House of Usher; Joe D’Amato’s Rosso sangue (1981) was sold as Zombie 6: Monster Hunter; and the film that it’s a semi-sequel to, Antropophagus (1980), became Zombie 7. Andreas Schnaas’ Zombie ’90: Extreme Pestilence (1991) has also been sighted under the title Zombi 7 and Amando de Ossorio’s La noche de las gaviotas (1975) has been sold as Zombi 8.

Who Were the Pinkertons?

Rebecca Onion, Slate

The court will ultimately have the last word, but the conflict does seem, at first blush, to be somewhat ridiculous: How many times have we seen Pinkertons in popular entertainment, from Deadwood to Boardwalk Empire to BioShock Infinite? And that’s only the fictional Pinkertons that have surfaced in recent years. The agency has a long “Appearances in popular media” Wikipedia section, and at least one historian, S. Paul O’Hara, has written an entire book on the agency’s evolving significance in public culture. Aren’t “The Pinkertons” ours now, part of our popular culture, to do with as we please?

Next Time on Maddd Science: When Genre Tropes Go Bad

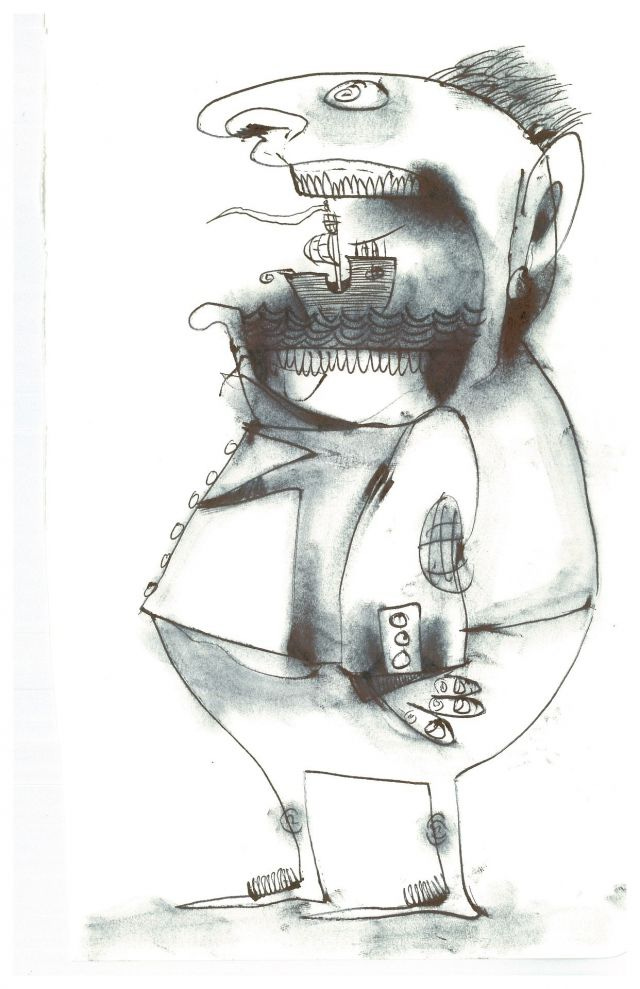

Header image: “adventure so close you can taste it,” by Daniel Williams.

Like this issue? Maybe forward it to someone you think would like it, too. My marketing budget just covers that and my twitter account. And if someone forwarded this to you, you can subscribe here!